Researchers have conducted an experiment on 900 people which shows intercultural connections between 25 different languages. This could be a breakthrough in the fields of linguistics and philology.

Have you ever tried to communicate with someone who doesn’t speak your language? Exchanging frantic gestures and impossible to understand words as you both become more and more frustrated? It usually seems like an impossible situation.

Well Aleksandra Ćwiek doesn’t think the barrier is insurmountable.

“There are things that connect us as humans that are deep in our cognition, deep in our nature,” says the doctoral researcher at the Leibniz Centre for General Linguistics (ZAS).

“We can show shapes with our voice.”

Ćwiek is completing a Ph.D. in iconicity in language and sound symbolism, and is interested in how sight and sound are connected.

For years linguists assumed that the connection between words and the objects they are attached to was arbitrary. For example, there is no link between the English word ‘dog’, or the French word ‘chien’, and an actual dog.

However, iconicity is an area that investigates whether or not there is a connection between what we say and how we say it. For example when we talk about something in the sky we use a high-pitched voice, or when we talk about something underground we use a low-pitched voice.

Other examples include words that are expressive of movement like ‘swish’, evoke patterns like ‘zig zag’, or onomatopoeic words which mimic sounds like ‘boom’.

“This is the beauty of iconicity, we can resemble,” Ćwiek says.

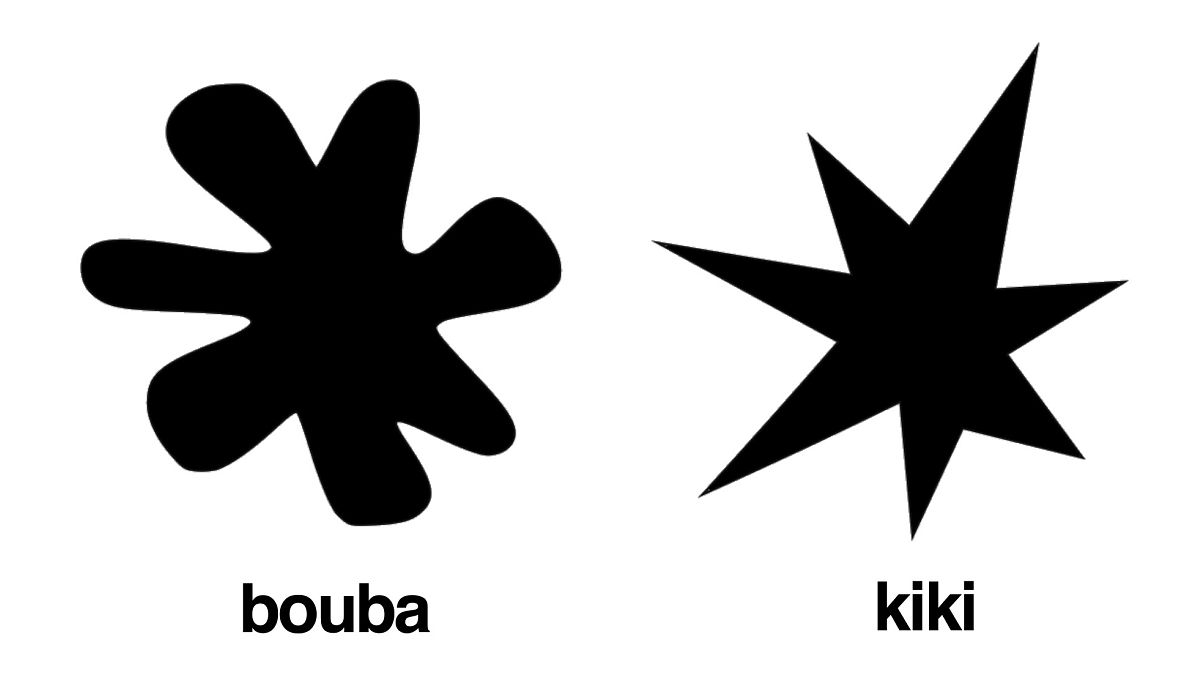

Bouba/Kiki and intercultural connections

The Bouba/Kiki experiment originated in 1929 when Wolfgang Köhler used the words ‘maluma’ and ‘takete’ to examine cross-modal correspondences or links between the senses. Köhler examined whether or not participants associated ‘maluma’ with a round shape and ‘takete’ with a spiky shape.

The methodology has since developed and the words have evolved into ‘bouba’ - associated with a round shape- and ‘kiki’ - associated with a spiky shape.

Different forms of the experiment have been done in different places including with non-literate communities in the Himalayas and Papua New Guinea, as well as with pre-literate children.

Ćwiek and her colleagues from a number of different institutions designed an experiment to conduct with people from around the world, hoping to establish the cross-cultural nature of the Bouba/Kiki effect.

“We took it to another level by using the same methodology across different languages,” she says.

Altogether, 900 people were tested across 25 languages.

“This is the first time that we have investigated that many languages with the same experiment,” says Ćwiek.

The multicultural research participants were presented with both the round and spiked images and randomly played either of the two words. They were then asked to assign the word they had been played to the form of their choice.

On average, more than 70% of the people tested confirmed the Bouba/Kiki effect. Speakers of 17 out of 25 languages as far apart as Japanese, Swedish, French and Zulu, systematically validated the effect.

The effect wasn’t proven universal however and the test failed for Chinese, Romanian and Turkish. Ćwiek has an explanation for that, though.

“There are linguistic mechanisms...that override the effect,” she says.

In Romanian for example there is a word for wound that sounds like ‘bouba’, the sharpness of pain associated with this sound may eradicate the connection to the soft round shape. A Turkish word for cute sounds like ‘kiki’ and the association with small cute things (like babies) may challenge the sound's connection to spiky images. Meanwhile, in Chinese ‘bouba’ and ‘kiki’ are not native syllables and may just have sounded odd.

“There might be languages that just forbid certain structures,” says Ćwiek.

What does Bouba/Kiki mean for the past and the future?

But whatever our linguistic leanings now, the experiment has exciting implications for the origins of language.

While Ćwiek doesn’t believe there was one original language - a ‘mother tongue’ if you will - she does believe that sensory crossover may indicate how language developed.

“These correspondences, I feel they are engraved in us in a way they might have helped us to build words at the very beginning.

“When we don’t share a language it’s easier to rely on resemblance than to rely on something very abstract. If the signal gets to you then you’re more likely to repeat it and it’s more likely to be coined as a term.”

These days iconicity is often used in marketing. Brands will take advantage of the warmth of ‘bouba’ in the mouth and the break of the airstream of the lungs from ‘kiki’ to create names that correspond pleasingly with products.

Overall though, the experiment proves a certain commonality of experience amongst humans. Ćwiek argues we should use our ability to draw with our voices to try and cross-cultural boundaries.

“It has a lot of power across languages. We focus too much on geographical borders; we are all humans.”