Brexit and Art Will new regulations and ongoing uncertainty continue to stifle the art market after the impact of Covid-19?

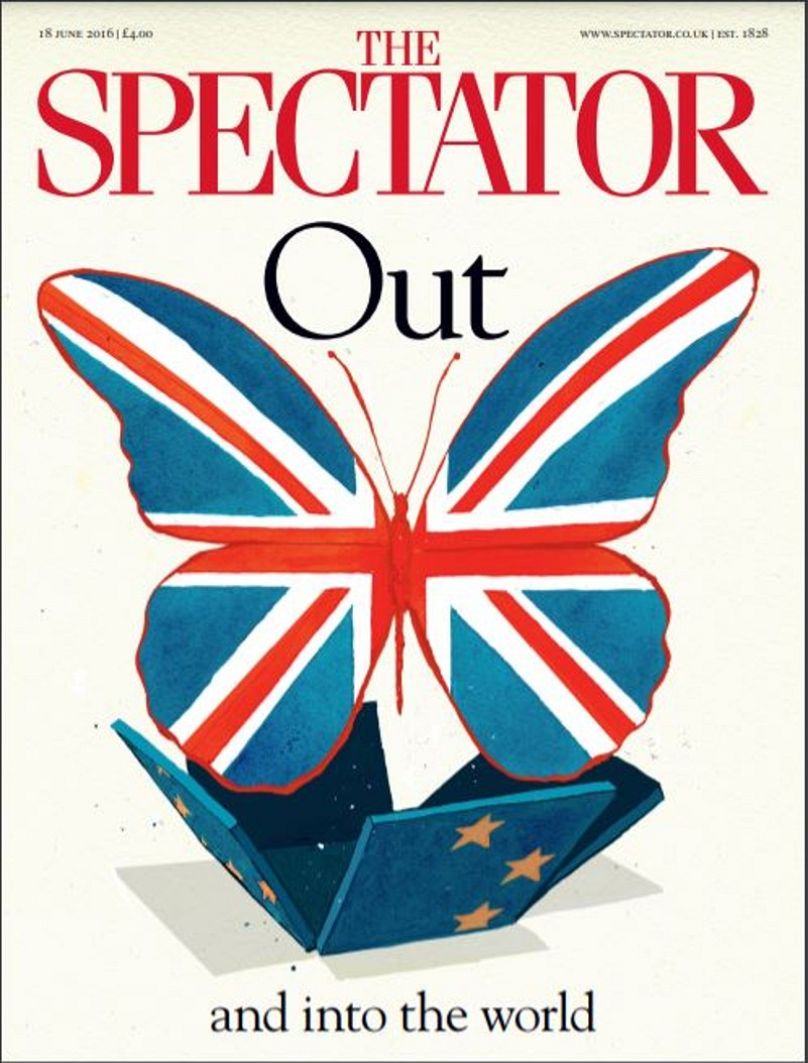

Earlier this month, The Spectator, a conservative British magazine established in 1828, sold an NFT of what its editor, Fraser Nelson, said is “perhaps the best-known” of all its front covers. Produced for the magazine’s 18 June 2016 edition by the political cartoonist Morten Morland, the image shows a Union Jack emblazoned butterfly emerging triumphant from a collapsing box dotted with EU stars. The text reads, “Out - and into the world”.

As Nelson has written, the cover acted as the magazine’s announcement that it was backing Brexit, only days before the UK public voted in the referendum that would see the country follow that course. The image was something of a hit with pro-Brexit Britons but was also relatively rare in being a professionally-produced, notable piece of artwork that fell on that side of the argument.

While The Spectator’s cover successfully got its message across to an appreciative audience, contemporary art produced in reaction to Brexit has tended to take a Remainer line. Not surprising, supporters of Brexit might say, given the internationalist, left-leaning art world aligns nicely with the kinds of liberal elites they were hoping to dethrone. For anti-Brexit Remainers, though, an alternative vision of Morland’s butterfly might have been an ascendent dusty moth, with a Northern Ireland-sized chunk missing from one of its wings.

As we all know, it has been a long journey since the butterfly burst out of its box. The protracted negotiations between the UK and EU over the former’s exit have led to post Brexit regulations finally coming into play at the same time as the continent has been dealing with the COVID-19 crisis. While UK consumers have become used to empty supermarket shelves, petrol queues and shipping delays, it’s not always easy to separate out Brexit-induced self-harm from the effects of the pandemic. Like other industries, the art world has faced a situation where Brexit and Covid-19 have come together to hit hard with a combination of blows. The most forceful strikes have come from the pandemic, but complications directly attributable to Brexit are also becoming apparent.

For UK and EU galleries, the biggest Brexit issue is now the increased cost, paperwork and effort involved in moving artwork between the two regulatory regimes. European galleries attending London’s Frieze art fair in October this year, for example, noted the increased difficulty of getting their artists’ work to what is the biggest annual event in the UK art scene.

Brexit is also starting to impact arts education, with EU students coming to the UK now having to pay the considerable tuition fees applicable to international students from the rest of the world. Correspondingly, UK art students have lost the easy access they once had to courses across the continent, some of which previously afforded them free tuition.

Whether such factors have a negative or realigning effect on the commercial art world long-term remains to be seen. Asked whether Brexit has negatively affected the art market from a UK perspective, a spokesperson for the auction house Christie’s was notably upbeat, saying “Our London sales are international; in this year’s (2021) Art Basel / UBS Report on the global art market, it was stated that 87% of the value of the UK market was made up of non-EU trade. So we remain confident that London will remain at the centre of the global art market.”

The spokesperson added that this year’s Frieze was well attended, with “a real ‘buzz’”, and that “many had travelled from around Europe and the US to attend.” They also noted that 2021 sales have been strong, with bidding activity in recent London auctions “fairly evenly split “ between Europe, Asia and the Americas.

The global nature of operations like Christie’s that sit at the top of the art market means they are well adjusted to having to deal with different regulatory regimes. Leading UK and EU galleries are also perfectly at home attending art fairs in the USA and Hong Kong, and in selling work to collectors in China and the Middle East. London’s central position within this system bodes well for the kind of “open, global Britain” that The Spectator editor Nelson suggests is embodied by Morland’s butterfly image. Even so, the spokesperson for Christie’s acknowledges that there have been "changes to adapt to because of Brexit."

"For example, those who have bought and sold via our Paris or London salesrooms, but are based in the opposite city, will notice the mechanics and processes for shipping and tax have changed. As a global business, we know the procedures as we use them regularly. Problems may arise with external suppliers (i.e. shipping) with the increased volume, but we have anticipated this with our regular suppliers and Christie’s team. For other players in our industry, though, it has been more challenging.”

Offering his perspective across the sea from the UK, Fons Hof, the longstanding director of the Art Rotterdam art fair, says that the combination of Brexit and COVID-19 has had a definite impact: “Yes, there is definitely a big difference. The Corona measurements for non-EU galleries made it difficult to participate in the last, postponed edition of Art Rotterdam in July. Also transporting the artworks has become a lot more complicated for English galleries. The small galleries in particular did not oversee all this and decided not to participate. Nevertheless, I expect that these English galleries will also get used to the temporary import of works of art when they do a fair in the EU. And with that, I think the participation of English galleries will normalise again in the future.”

With the 23rd edition of Art Rotterdam set to take place from 10 to 13 February 2022, Hof believes “that the worst is behind us regarding COVID-19 and Brexit. Although strict measurements are now expected again, and some art fairs may have to be moved again, the organisations have much more experience in dealing with the Pandemic and everyone has become much more flexible. In addition, I think that museum visits and a visit to an art fair are easy to regulate and adapt to the conditions of a safe visit.”

The full impact of Brexit on the European art world is unlikely to be known until the dust has settled on new regulations that came into force in 2021 and organisations have had time to assess how restrictions on residency and working rights, as well as the movement of both people and artworks between the EU and UK, are affecting their operation. Also unknown will be the impact of new arrangements yet to be agreed upon, more arm-wrestling between the politicians involved, and the possible retraction of things currently in force.

Like the rest of us, the art world will have to play a waiting game. It’s possible that the consequences of Brexit at a macro level may not be too great. On an individual level, though, there will be plenty of people in art sharing in the burden of no longer having the same level of freedom to live, work, study and travel as easily as they once did between the UK and its European neighbours.