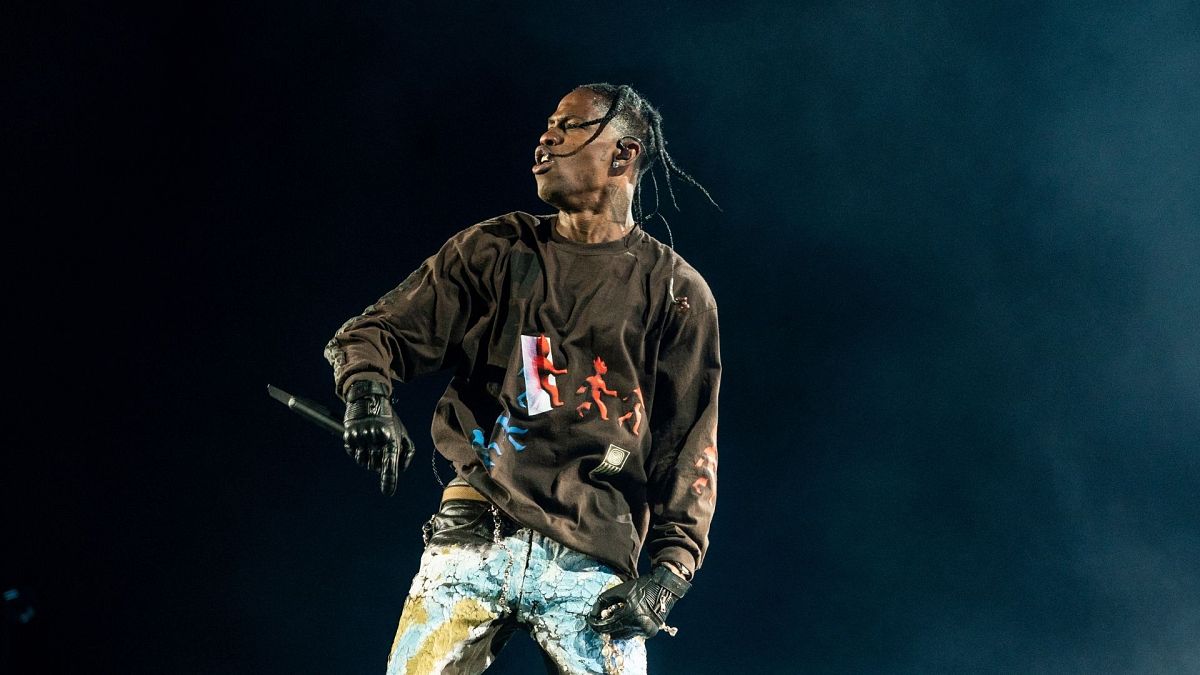

Eight people lost their lives in a crowd surge at a festival organised by rapper Travis Scott last weekend. The youngest was 14 years old. Euronews asks industry leaders in concert safety about the tragedy and how it could have been prevented.

Last weekend, 50,000 fans attended rapper Travis Scott’s Astroworld festival with the expectation that they would be safe from harm.

Paying upwards of $365 (€315) for a ticket, the event should have been a hip-hop lovers dream, especially for those who had yet to attend a concert in Houston, Texas, since COVID took hold.

This turned out to be the complete opposite for masses of the rapper’s fans. Video footage from the event shows various pockets of the audience in distress as staff and concertgoers stand oblivious further down the field.

By the first song, eyewitnesses describe finding it “difficult to breathe,” and less than an hour later several people had suffered serious injuries, some entering cardiac arrest.

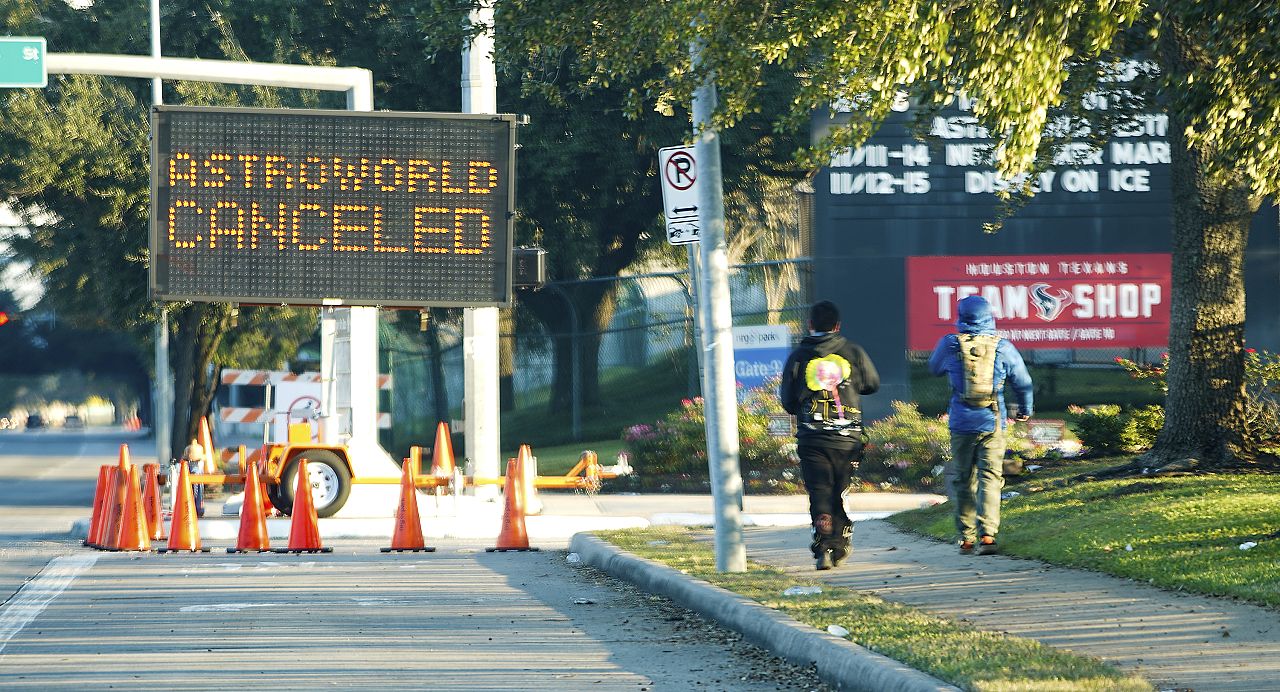

An investigation is underway with assistance from the FBI.

What do we know so far?

A number of ticketless fans bypassed security in order to gain access to the concert, and that Scott’s set continued for a further 40 minutes after the alarm was raised, despite police pleas.

We also know from a 56-page event document that Scott's team had plans in place for terror threats and extreme weather. When it came to the issue of crowd surges, there were none.

Astroworld's death toll has risen from 8 to 10 people since the evening of the event. All 10 victims have been identified and named - the youngest aged just9 - as promoters scramble to mitigate an unfixable tragedy spawned from a love of music.

Eight fans were declared deceased on the night of the show. Another, 22-year-old college student Bharti Shahani, passed away in hospital from critical injuries 5 days later.

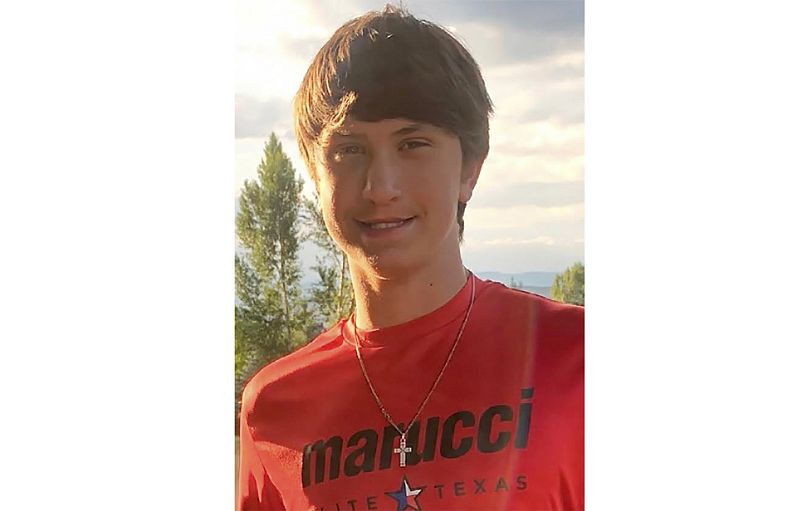

Ezra Blount is the latest confirmed fatality - the 9-year-old has been in a medically induced coma since the night of the show, and was confirmed dead by his family on November 15.

Scott has said he will cover funeral costs for each victim.

We spoke to Europe’s leading figures in crowd safety to understand how the disaster unfolded.

‘The grief, the tears, the priests on stage - I have seen it all’

A show stop: you might not be familiar with the term, but any regular concert goer is likely to have experienced one at least once.

The stage lights go up, the performer uses their influence to tell everybody to take a few steps back, in order to free up room for fans that look like they are struggling, dehydrated, even unconscious

Its guiding principle is simple - if they don’t listen to the person they are paying to see, the show stops. The whole operation takes less than a minute in most instances because fans are willing to listen.

Show stops are relatively new invention in the world of live music, first pioneered by Steve Allen, head of Crowd Safety, a UK-based consultancy firm that has overseen audience protection for the likes of Eminem, Kasabian, and the Red Hot Chilli Peppers.

His greatest challenge landed with a number of years spent heading tour safety for Britpop legends Oasis.

“When we were doing Oasis years ago in the late 90s, their crowd went mental. It was absolute full on energy and I had a genuine belief that people were going to die.”

Something desperately needed to change. It was then that Allen conceived of a process for future artists to follow that was circulated throughout the industry.

“I know what can happen. I was there at Roskilde (a Danish festival where 10 people died during a Pearl Jam performance) in the morning after that death, and I gave the technical reasons why Oasis wouldn't be performing.

“The grief, the tears, the priests on stage - I have seen it all.”

Videos of crowd surges at Oasis's stadium concerts are frequently used in crisis training.

Allen has stopped concerts upwards of 25 times in his career. None of them fell into the criteria of a “bum shout” - an industry term for halting a performance without good reason to, subsequently disrupting its flow.

“With crowds in distress, it doesn't matter how big you are, you could be 6 foot six and 300lbs. You are not getting out of there. The only way you're getting out of it is it being stopped.”

A 56-page event operations plan for the Astroworld music festival included protocols for dangerous scenarios including an active shooter, bomb or terrorist threats and severe weather. But it did not include information on what to do in the event of a crowd surge.

Videos of artists from all genres calling for said ‘show stops’ have reached every corner of the internet as grieving people seek evidence that the tragedy could have been dealt with differently.

Who is responsible for calling a show stop?

Who would have had the executive authority to call a show stop where Astroworld is concerned?

Allen describes in great detail that every event has clear cut plans on who communicates with whom in a crisis. ‘Spotters’ are appointed within security to view large crowds from a height, who are then expected to relay this information to the artist’s team.

An experienced, well-coordinated team will have plans in place for every possible outcome.

Chris Hannam, who wrote some of the world’s first books on the subject, vehemently agrees.

In the event of a crowd crush, concert crews have around 3 minutes before injuries become fatalities, he explains.

Hannam was once responsible for managing potential instances at Glastonbury’s two main stages. He subsequently founded Stage Safe, a global health and safety company that has coordinated safety for the tours of The xx, Blur, and Blackpink.

Important distinctions to make

Fans of Scott’s argue that the 50,000-strong crowd was too large to be able to observe disturbances due to frequency of crowdsurfing and moshing that takes place.

Traditional moshing and crowd crushes are very different things. Moshing - the process of deliberately colliding with fellow concertgoers to high-energy music - has its own rules that prioritise the safety of others. Both experts concur.

Another issue both desire to make clear is the difference between crowd management and crowd control, as the terms have been used interchangeably in some media coverage.

Crowd management facilitates the ease of movement for fans travelling around an event - in this case, those responsible for barrier admissions. Crowd control are the people that step in if there are any signs of the event getting chaotic.

If all of this applies, why did the show continue?

A tangible answer to this question is pending further investigation.

The Houston Chronicle alleges that the show’s promoter agreed to stop the show as soon as it was declared a ‘mass casualty incident.’

One video of a fan pleading with staff to provide assistance has been viewed 10 million times.

Scott is seen to acknowledge what is happening at several points during his headline set. The entirety of it was live-streamed on Apple Music.

The arrival of an ambulance into the audience - something Hannam says would never happen in Europe as an unsafe act in itself - was impossible to ignore.

“What the f**k is that?” he asks, gesturing to an ambulance making its way through the crowd. After an onstage approach from two members of his team, he continues the performance.

Still - who is responsible for calling a show stop if the artist is unaware of the events taking place on the ground?

Hannam emphasises the person needs to be someone trusted by the artist

“A stage manager or somebody appointed will stop the performance, and then stewards can do their bit on rescuing, which is what they're trying to do. Or should be trying to do.”

Mixed responsibilities lie between Travis Scott and Live Nation

There has been some speculation that safety protocols weren’t followed as a result of Scott’s inexperience running regular events - the festival is still in its relative infancy, having debuted in 2018 and postponed as a result of COVID in 2020.

Both experts make it clear that to suggest this is to exhibit a fundamental misunderstanding of how live events are conducted.

The event was run in partnership with Live Nation - the biggest music promoter in the world - who would have been in charge of planning ahead and communicating their intentions with the headline act.

“It's not promoted by Travis himself. You've got a major promoter that has got benchmark guidelines on what to do,” explains Allen.

Override systems are present at the side of the stage that are able to enact this function. If a clear channel of communication hasn’t been made between crew and artist, there are several people with the power to stop what is happening by cutting sound from the speakers.

Hannam stands firm in not speculating, but asserts that from his experience: “Live Nation, like any other big promoter, are out to make money.”

“One of our complaints often is: they're more interested in making money than they are over audience safety. They make great claims and things like this, but we know damn well what happens in reality.”

Live Nation Entertainment finished 2020 - a year plagued by the closure of entertainment and cultural venues - with a net income of $1.828 billion (over €1.5 billion).

The problems with planning a major event

Travis Scott is no stranger to a raucous performance - from sailing to the EMA’s on an animatronic bird to spitting on fans that steal his Yeezys.

A video sits on Youtube with 4 million views to entertain those with a fascination for his stunt pulling.

Scott has been twice arrested for encouraging fans to break through security barriers at his shows, and was sued in 2017 for encouraging a fan to jump off a three-storey balcony.

It goes without saying that these issues would have been brought to Live Nation’s attention when coordinating Astroworld with Scott to prevent further litigation.

Lawsuits are piling up against the rapper as the week trudges on for the friends and family of those affected. The largest so far stands at $1 million.

“Let's face it,” Allen explains, with a hint of exasperation. “50,000 people is a major event, it's a greenfield site, one of the big major events for that area that's probably happening out of lockdown.

“I would be looking at how the crowd profile, the demographics of the artist, i.e. have there been historical situations with this artist? What are the types of issues we face? How quick was it sold?”

And yet - planning isn’t always enough. Plans are great on the day, but keeping fans safe comes down to constant monitoring of live shows so they don’t descend into chaos.

The “embryonic phase of a life-threatening situation,” he calls it.

Ultimately - how did this happen?

"The crowd began to compress towards the front of the stage, and that caused some panic, and it started causing some injuries,” according to Houston Fire Department Chief Sam Pena.

“It could be overcrowding, it could be just bad management of the crowd,” says Hannam.

“You usually find that there are several different things happening at once. Little tiny things, but they all go together to make one big thing. I think that's what's happened here. We've got lots of little, little hazards and little things taking place. And when you put them all together, you've got something huge happening.”

Allen is still finding the events of last weekend extremely difficult to reckon with. After decades spent advancing safety awareness in the events industry, the conversation returns to the subject of needing the right people in charge.

“If you think about it, when we get on a plane, which has 400/500 people on it. The person in charge of that is a person that has got a wealth of experience, and years of training.

“Any emergency. And that's just 400 or 500 people. Here you’ve got 50,000 people. So surely at that critical moment, you want to ensure you've got the right people.

Horrifying details about the incident emerge as each day passes. We now know a nine-year-old boy has been put into a medically induced coma following injuries sustained at the festival.

Live Nation is in the process of refunding people that attended Astroworld last weekend and creating a medical fund for those affected physically and mentally.

They provided Euronews with the following comment: “We continue to support and assist local authorities in their ongoing investigation so that both the fans who attended and their families can get the answers they want and deserve, and we will address all legal matters at the appropriate time.”

Scott’s management did not respond to requests for comment.