In the wake of Spain's €1 million Planeta literature Award controversy, we reflect on the authors of times past that used pen names, and why they chose to.

Earlier this week it was revealed that Carmen Mola, author of a number of widely praised Spanish crime thrillers and recipient of the world’s most expensive literary prize, was actually the fictionalised nom-de-plume of three men.

Jorge Díaz, Agustín Martínez and Antonio Mercero, all known primarily for their work in screenwriting, stepped on stage at the 2021 Planeta Prize to collect a cheque for €1 million.

‘Carmen Mola’ was awarded the cheque for a book titled La Bestia, or The Beast, an unpublished work set in the 19th-century cholera epidemic.

Literary critics have spoken out to express their concerns about why the group - whose work has been selected by the Women's Institute as essential feminist reading - felt the need to hind behind an alias.

They have since spoken out about the controversy, insisting they hid behind a name, rather than a gender.

Why do authors use pen names?

This discovery might be one of the few known examples of the 21st century, but writers have been hiding behind pseudonyms for a number of reasons since literature was first considered a marketplace.

Perhaps there are fewer reasons to do so now - indeed, JK Rowling wrote under the name Robert Galbraith just to 'be liberated' - but this week's Planeta shock shows that pen names are still effective.

Are the reasons less understandable, as it has been argued, than from those that did so in 19th century England? That's for you to decide. How often are we given the opportunity to become someone else entirely? If you’re an author, it’s pretty easy.

Here are some examples you might have forgotten, and why the writers did it.

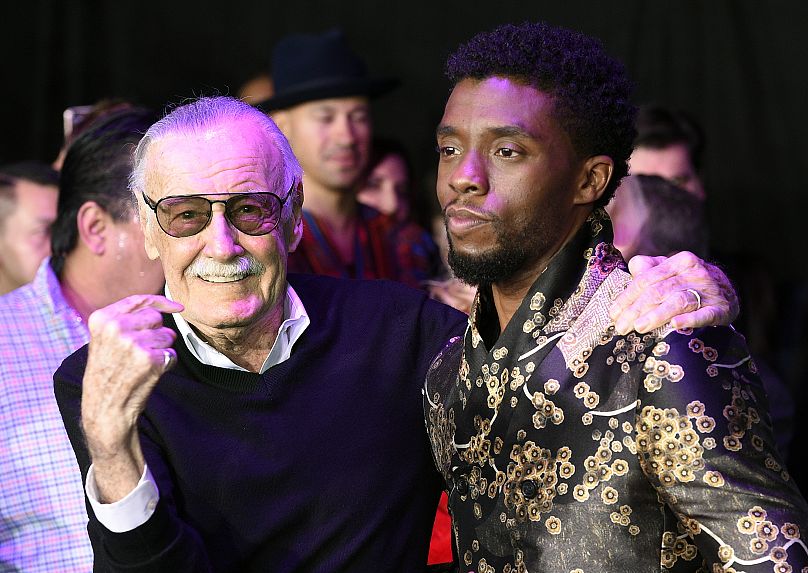

Stanley Martin Lieber became: Stan Lee

Any comic book fan beams at the mention of the late Stan Lee, but it was never the Marvel legend’s intention to run the course of his career creating superheroes.

He initially intended to use his real name for writing work beyond the realm he achieved unquantifiable amounts of success in. The revival of the superhero-era in the late 1950s left him with no choice but to accept that this was his calling, and he later changed his legal name to reflect that.

Lee went on to become responsible for changing Marvel Comics from a misunderstood faction of the publishers to a worldwide, multi-billion euro entity.

Mary Anne Evans became: George Eliot

Mary Anne Evans emerged from Victorian Britain as one of its most respected authors, penning seven novels throughout her writing career, such as Middlemarch and Adam Bede.

Yes, female authors were actively publishing their work at this time, and Evans had the option to do so. But she did what she felt was necessary to avoid the reductive stereotypes that came with writing as a woman - female authors were often caged to romance novels.

From that, and a desire to shield herself from public scrutiny, George Eliot was born,

Agatha Christie became: Mary Westmacott

Female writers don’t always switch to pen names to avoid gendered expectations of their work.

Sometimes, they just so happen to be really successful and need a break from it all. Take Agatha Christie, who in 1950 reverted her literary identity back into the unknown in order to explore different subject matters. She remained as a woman, drawing from distant family names and her middle name to create the identity.

Mary Westmacott’s six novels allowed Christie to step away from crime fiction and explore the nitty-gritty of love, relationships, and human psychology. She kept the name successfully hidden for twenty years.

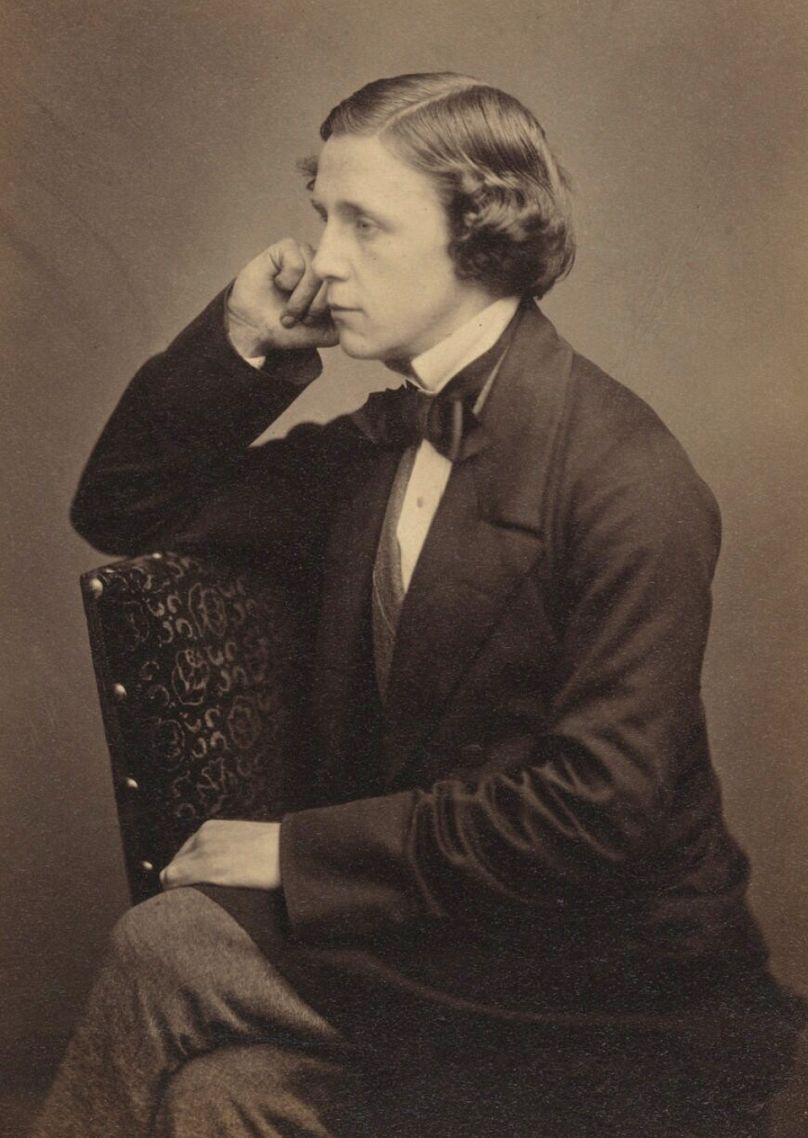

Charles Lutwidge Dodgson became: Lewis Carroll

The creator of Alice’s Adventures In Wonderland opted for the name we know him as today to be modest.

The man we know as Lewis Carroll was happy writing academic work under his real name but drew the line at fiction in order to retain some privacy. Dodgson translated his first two birth names into Latin - Carolus Lodovicus - and then anglicised them in reverse to become the author of some of literature’s most mind-bending works.

Any letters addressed to his pen name at his workplace, Oxford University, would be firmly rejected upon the insistence that no such person existed there.

The Brontë sisters became: Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell

The Brontë sisters are known in our culture today by their real names, but this wasn’t always the case.

During the infancy of their literary careers, the trio was advised by publishers to operate under male pseudonyms for higher credibility.

Despite giving in to the decision, Charlotte, who went by the name of Currer Bell, had her first novel, The Professor, rejected under the alias. It didn’t take long for momentum to surround her follow-up, none other than Jane Eyre, and the hype was enough to get the sisters to admit to their cover-ups as rumours swirled around London literary circles.

Stephen King became: Richard Bachman

Stephen King’s switch to a pen name came as a result of a social experiment. Well into his career as a renowned horror writer, he was told by publishers that readers weren’t interested in picking up more than one new book from an author each year. Status didn’t come into question, whether you'd written The Shining or not.

He put this theory to the test, assessing whether people would purchase new work from him based on talent, rather than fame. The resulting work, Richard Bachman’s debut novel Thinner, sold 28,000 copies throughout 1984.

It paled in comparison to the millions of copies on the shelves of King readers globally. As soon as King revealed the work was his sales of Thinner increased tenfold, though the accompanying feature film didn't fare as well.

Sylvia Plath became: Victoria Lucas

Sylvia Plath's The Bell Jar was the American poets only work of fiction, released shortly before her suicide at the age of 30 in 1963. Its semi-autobiographical depiction of mental illness has been a mainstay in university curriculums and literary criticism ever since.

Plath herself found the book's subject manner too dark and damning for the people close to her to ever find out it was based on her experiences. The story gets blurry from here, but friends have since confirmed she was especially concerned about her mother.

In order to aid this, she released it as Victoria Lucas, separated entirely from her work as a poet.