Polls suggest that Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan seems set to lose the upcoming elections on 14 May. Still, his past record tells us that he might do everything he can to reverse his fading chances, Hamdi Fırat Büyük writes.

It has been a long time since the citizens of Turkey awaited the high-stakes parliamentary and presidential elections with such bated breath.

President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, who has been ruling the country for 21 years, is set to face a united opposition candidate on 14 May, and this time, his chances look slim due to never-ending political and economic crises that were only deepened by the tremors costing more than 10% of the country’s 2023 national GDP.

The devastating twin earthquakes in early February that killed more than 50 thousand people and left millions homeless have only furthered a major decline in his popularity, with Erdogan expected to pay the price of what has been deemed a largely inadequate emergency response.

Right now, polls suggest that Kemal Kilicdaroglu, the leader of the main opposition Republican People’s Party, or CHP, and the joint presidential candidate of the Nation Alliance, leads the presidential race with at least 10 points ahead of Erdogan.

Kilicdaroglu is also expected to get support from smaller parties as well as Turkey’s third-largest bloc, Labour and Freedom Alliance, led by the pro-Kurdish Peoples’ Democratic Party, HDP.

Regardless of the dark clouds gathering fast, Erdogan and his People’s Alliance seem unphased and certain of yet another victory. Many wonder how come — but the answer can be gleaned from his past record.

In Erdogan's eyes, the state is himself

For Erdogan, a victory would represent a go-ahead to cement his autocratic rule once and for all. A win would provide him with a way to rule Turkey for good, moving the country further away from the West and the EU and destroying every form of opposition against him.

For the opposition, the 14 May elections are seen as the last chance to preserve Turkish democracy and prevent the country from sliding further towards autocratic rule.

During his more than two decades in power, Erdogan established near-absolute control over state institutions, especially after an executive presidency was introduced in 2018, giving supreme powers to his office.

Since then, people with links to Erdogan and his party have been systematically placed in positions of power in the judiciary, police, army, and other state institutions.

Moreover, while other parties have only donations to rely on in addition to humble financial support from the country's treasury, Erdogan and his party control all of the state's financial means.

The Turkish Presidency's Communications Directorate alone has spent nearly 233 million liras (approx €11.3 million) in the first two months of 2023 — a 274% increase to the same period in 2022.

In fact, the Communications Directorate — although technically a state institution — proved to be the Turkish president’s tool for propaganda and a pressure mechanism on what is left of Turkish media.

As the vote nears, the state budget will increasingly serve for Erdogan’s elections games in addition to providing him with a major platform for media appearances, as more than 90% of the Turkish media scene is owned or controlled by the government.

The remaining independent media outlets have started to feel the pressure after being hit with heavy fines.

Since the earthquake disaster and with the approaching elections, Turkish TV stations have been heavily sanctioned and fined for their critical coverage ahead of the vote by the Radio and Television Supreme Council, RTUK, the state agency that monitors — and sanctions — radio and television broadcasts.

Social media warfare and disdain of Twitter

But the media campaign will not end there. The Turkish government has already established a control mechanism on social media with draconian laws and regulations.

The government also banned Twitter during the earthquake disaster, saying that it was to blame for the increase of disinformation following the public anger against the government’s ineffective and slow disaster response.

Experts, politicians, and commentators criticised the ban, saying that Twitter was the main source of communication for many people searching for survivors and victims, as well as for local and nationwide aid campaigns.

Erdogan's government has toyed with limiting or outright blocking access to social media in Turkey ever since activists widely used platforms like Twitter to organise and communicate during the 2013 Gezi Park protests in Istanbul.

The protests posed a huge challenge to his authority at the time that ended with a brutal police crackdown causing several deaths among the demonstrators, causing Erdogan to label Twitter as "trouble", accusing it of spreading "unmitigated lies".

He followed up by openly criticising Twitter, calling it "Twitter, mwitter!" and threatening to "eradicate" it in front of his supporters in the run-up to the municipal elections in 2014.

Officials then banned it just days before the vote on the grounds of allegedly allowing posts "insulting Turkish citizens" to remain on the platform and a law allowing the Telecommunications Board to block any website or social media network for anything it believes to be "privacy violations".

Now, it is not certain that the government would not attempt to impose a similar ban before, during or after elections using "disinformation" as an excuse.

This time, internal subversion is not out of the question

In the meantime, more and more reports suggest that Erdogan and his party are trying to subvert the platform from within.

In the last few months, there has been a significant increase in Twitter accounts posing as news outlets without specifying members of their editorial board, journalists, or even linking to a website.

These accounts, which have hundreds of thousands of followers, are allegedly controlled by the troll armies of AKP.

More interestingly, several influential commentators, analysts and academics revealed that dozens of fake accounts using their names have been created in the last weeks.

They claim that these accounts — again, controlled by the government trolls — aim to manipulate Twitter discussions on politics and upcoming elections.

Bots and fake accounts are also reportedly advocating for other politicians, such as Muharrem Ince, a former CHP official and 2018 presidential candidate, who is expected to take some of the votes that would otherwise most likely go to Kilicdaroglu.

Fears of election fraud spike

Increased fears of possible election fraud are not baseless hysteria. It would be naïve to believe there would be no attempts at it considering a record of malversations and questionable calls by authorities in Erdogan's times.

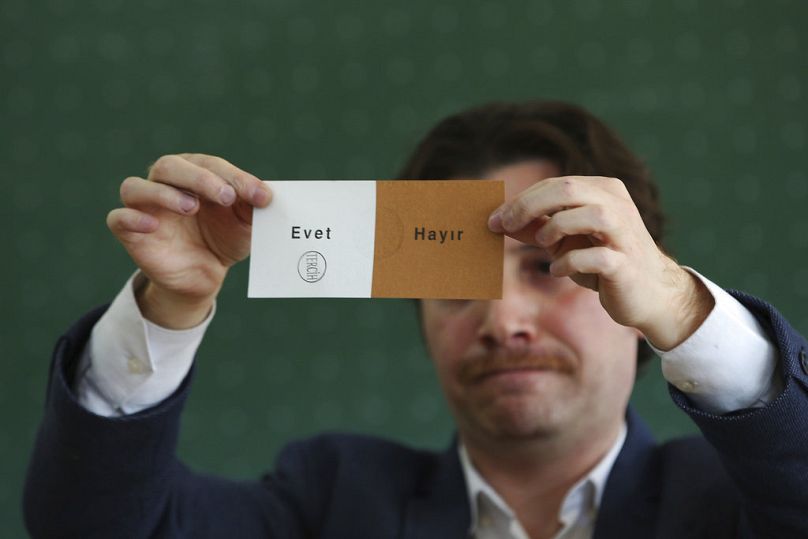

Most recently, in 2017, the Turkish Supreme Election Council, or YSK, reportedly accepted up to 2.5 million unsealed ballots — which could have been easily manipulated — in a referendum that allowed Erdogan to undermine the country's parliamentary system and push through the aforementioned executive presidency.

The YSK decision was supported by the AKP. The opposition, rights groups and international organisations condemned it.

In 2019, Erdogan made the unthinkable after he lost Turkey’s important cities, including Istanbul, Ankara, Antalya and Adana, to the opposition in local elections.

YSK, fearing Erdogan, annulled Istanbul’s mayoral vote due to alleged irregularities. However, district and city council elections — in which Erdogan’s party held the majority — were not annulled even though people voted at the same time with the same ballot boxes.

In the second round, Erdogan’s candidate still experienced a humiliating defeat against Istanbul’s popular mayor Ekrem Imamoglu.

What will happen to the votes from the earthquake-affected areas?

This time, one major issue stems from the fact that it is not clear how people will cast their votes in the areas affected by the earthquakes, as there are almost no standing buildings in some towns and cities.

Some 2 million people have been forced to migrate to safer areas, but only 345,000 people have self-registered in other cities for elections since.

In the earthquake-struck eastern Turkey, Erdogan allied with the Kurdish nationalist and Islamist Free Cause Party, HÜDA PAR, citing election safety in affected areas would benefit from the alliance.

HÜDA PAR is known to have ties to Hezbollah’s Turkish branch, held responsible for the assassination of hundreds of people, including intellectuals, journalists and academics, in the 1990s. It is also a designated Islamist militant terror group by the US and many Western countries.

Fears now abound that Erdogan might use HÜDA PAR to use the chaos to his advantage through illicit means, be it ballot theft or intimidation of voters.

Moreover, Russia — which has been accused of malicious influence on several elections across the world, including the 2016 US presidential election — clearly supports Erdogan as his government remains the only bridge for Russian trade following the West's sanctions over its invasion of Ukraine.

Last but not least, Erdogan passed a new election law last year that openly favours his party and allies.

In addition to the detailed mathematical calculation on how AKP could get more seats in the parliament with fewer votes as a result of the changes, the election boards’ structure was tinkered with as well.

Under the previous law, the most senior judge acted as the head of the district election board, but the new draft law suggests that first-category judges can now lead the election boards, meaning it's the professional category and not seniority that determines who gets to serve.

Following the failed coup attempt in Turkey in 2016, thousands of judicial officials were dismissed from their posts as part of the government’s crackdown on opponents, and the ruling coalition was accused of favouring their allies while appointing new judges and prosecutors.

Most of these new judges will be presiding over the district election boards, which could then repay the favour to those who appointed them, ignore any attempted fraud, or even participate in it themselves.

Opposition must be ready to play ball

Erdogan proved himself as a political strategist, winning under unexpected circumstances on several occasions.

This time, however, the united and growingly optimistic opposition is bound to be the first real test — and it might prove to be a test for both.

Kilicdaroglu united most of the opposition parties behind him, but he is known for his election defeats against Erdogan.

While he won one local election victory in 2019, Kilicdaroglu lost four general elections, two referendums, and two local elections against Erdogan, bringing the total between the two over the years to 8-1 in favour of Erdogan.

And despite the big lead in the polls, pre-election polling has also misguided both politicians and voters in the past.

In 2022, Hungarian strongman Victor Orban seemed to be on the brink of losing elections against a united opposition.

Yet, in the last weeks prior to the vote, Orban forged a comeback and brought another surprising victory to his party, cementing his control over Hungary despite the illiberal policies that he promotes.

In a highly polarised country like Turkey, polls can also cause people not to go out and vote on election day due to their confidence in a victory.

Whatever polls say, Erdogan has a strong voter base of some 30-35%, and he knows the profile of his electoral body very well while having every means to expand it.

The opposition, however, is very diverse and has less experience in working together. Just agreeing on the joint candidate could almost have ended the opposition’s alliance only two weeks ago — a tell-tale sign that not everything is as rosy as one would think.

Erdogan knows this, too, and will try to manipulate the opposition parties’ differences, especially regarding the Kurdish issue and the relationship with the pro-Kurdish HDP.

Erdogan still has cards up his sleeve

All things considered, the security and resilience of the electoral process must be the number one priority for opposition parties and civil initiatives between now and mid-May.

The 2019 Istanbul election and the relentless work of Imamoglu and CHP’s provincial branch chair Canan Kaftancioglu have done to ensure the vote's legitimacy should be seen as an example.

Without their effort, Istanbul could still have been ruled by Erdogan’s AKP.

If the opposition wants to win, they, together with everyone who believes in the salvation of Turkish democracy, should not be passive and must jointly build up their defences against Erdogan’s games before, during and after the elections.

Because even if Kilicdaroglu wins, it will only be over once Erdogan says so and admits defeat.

After all, two decades later, he will be hardly ready to give up on power without playing all of his remaining cards — and he still has plenty of those up his sleeve.

Hamdi Fırat Büyük is a journalist and political analyst working with the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network (BIRN).

At Euronews, we believe all views matter. Contact us at view@euronews.com to send pitches or submissions and be part of the conversation.