Human rights experts have accused the army of creating a "digital dictatorship" through internet shutdowns and surveillance since last year's coup.

Myanmar's deposed leader Aung San Suu Kyi has been moved to prison from house arrest, the military junta confirmed on Thursday.

Suu Kyi is now reportedly being held in a prison compound in the capital Naypyitaw, separate from other detainees.

The elected leader was arrested on February 1 last year when the army seized power from her National League for Democracy government.

She was initially held at her residence in Naypyitaw but was later moved to an undisclosed location, generally believed to be on a military base.

A spokesperson for the ruling military council told reporters that Suu Kyi was moved on Wednesday to the main prison in Naypyitaw in accordance with the law and that she is being held in “well-kept” circumstances.

The 77-year-old is being tried on multiple charges, including corruption, and has already been sentenced to 11 years imprisonment on various charges.

Her supporters say the charges are politically motivated to discredit her and legitimise the military’s seizure of power.

Suu Kyi's upcoming trials are now expected to be held in the Naypyitaw prison facility. She faces 11 counts of corruption, each of which carries a maximum prison sentence of 15 years, and an election fraud charge, which carries a maximum sentence of three years.

What's happening in Myanmar?

The military takeover in Myanmar has triggered peaceful nationwide protests that security forces have cracked down on with lethal force.

According to the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners, more than 2,000 civilians have been killed and around 11,000 others detained by the army since February 2021.

The army claimed it seized power because the November 2020 election — won by Suu Kyi's party — was marred by widespread fraud. The allegations were not corroborated by independent election observers.

The ruling military council has now said it plans to hold new elections around the middle of next year, but critics have expressed concern that such polls are unlikely to be free and fair.

Tom Andrews, the UN special rapporteur on human rights in Myanmar, said that the military has been working hard to “create an impression of legitimacy” after ousting Suu Kyi’s government.

“Any suggestion that there could be any possibility of a free and fair election in Myanmar in 2023 is frankly preposterous,” he told at a news conference on Thursday.

Suu Kyi has previously spent nearly 15 years under house arrest in Yangon under a military government.

A 'digital dictatorship'

Since the start of the coup, military authorities have also used internet shutdowns to block information from being communicated within Myanmar and beyond.

More recently, the junta has also shut down the internet in localised areas to target pockets of resistance in a certain town or region.

"Over time, the junta has experimented in different ways to enforce their dictatorship through the digital sphere," said Alp Toker, the founder of Netblocks.

"They have tried every conceivable method to keep people from communicating amongst themselves and to the outside world.

"These internet shutdowns, whether localised or national, are closely associated with military raids, forced disappearances and are driven into people's minds as a form of fear and control."

Phil Robertson, the Deputy Asia Director at Human Rights Watch, told Euronews that the junta has carried out a "systematic plan" to restrict people's online movements

"This is all about trying to hide the atrocities, such as burning down villages, shooting people, mass arrests, and abuses in custody," he said.

"It certainly makes it more difficult for the research and investigations that we want to do."

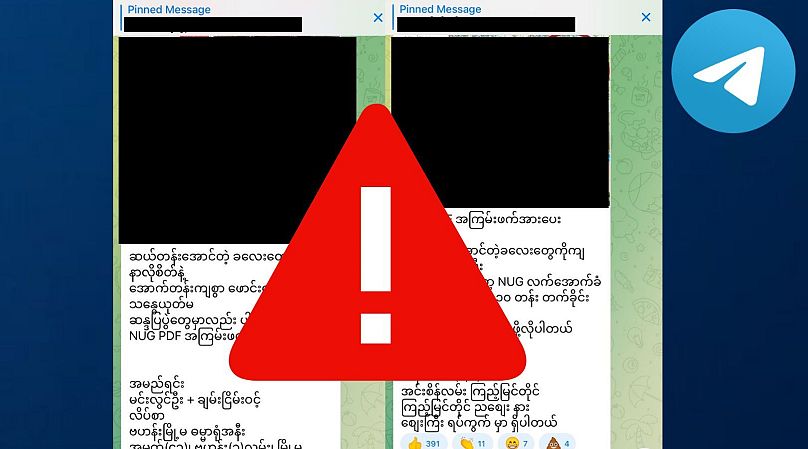

Major social media platforms, such as Facebook or Telegram, have become vital tools of communication for civilians in Myanmar, but have also been used to spread online misinformation, and facilitate violence.

Pro-military vigilante groups have appeared online, targeting regime opponents by sharing their personal information and contact details.

"What we're seeing is targeted surveillance against people considered to be activists," Robertson said.

One such account on Telegram — which has over 50,000 followers — has contributed to the arrest and even murders of high-profile regime opponents after posting their addresses online.

Meta banned the Myanmar military shortly after the coup began and has also removed Facebook accounts representing military-controlled businesses.

But analysts say the company has failed to prevent "hate speech" targeting anti-military protesters.

"Social media platforms haven't done enough so far in terms of having staff who understand the language and local crises, and can really get involved in complaints or abuse, harassment, and torture," Toker told Euronews.

'Suffering in silence'

In February, the European Union sanctioned several top officials in Myanmar, as well as a lucrative state-owned oil and gas company that has helped fund the military takeover.

The bloc has said that it is "deeply concerned by the continuing escalation of violence in Myanmar and the evolution towards a protracted conflict with regional implications".

But a recent UN press release has accused the international community of "standing quietly by" and urged countries to impose more targeted sanctions.

"The reality is that Myanmar is among the worst of the worst across the globe," Robertson told Euronews.

"We need sanctions restricting the sale or supply of dual-use surveillance technology, the things that the junta are using to try and track down various political activists."

"There should be a lot more pressure on companies that are selling things to the Myanmar military that they can use against their own people."

Netblocks, which has been documenting internet disruptions in Myanmar since the start of the coup, is also calling for more action.

"Attention has been somewhat divided internationally with the Ukraine war, and that means that Myanmar has suffered in silence in the last few months," said Toker.

"We need to find ways to reconnect people in Myanmar and let those voices be heard."