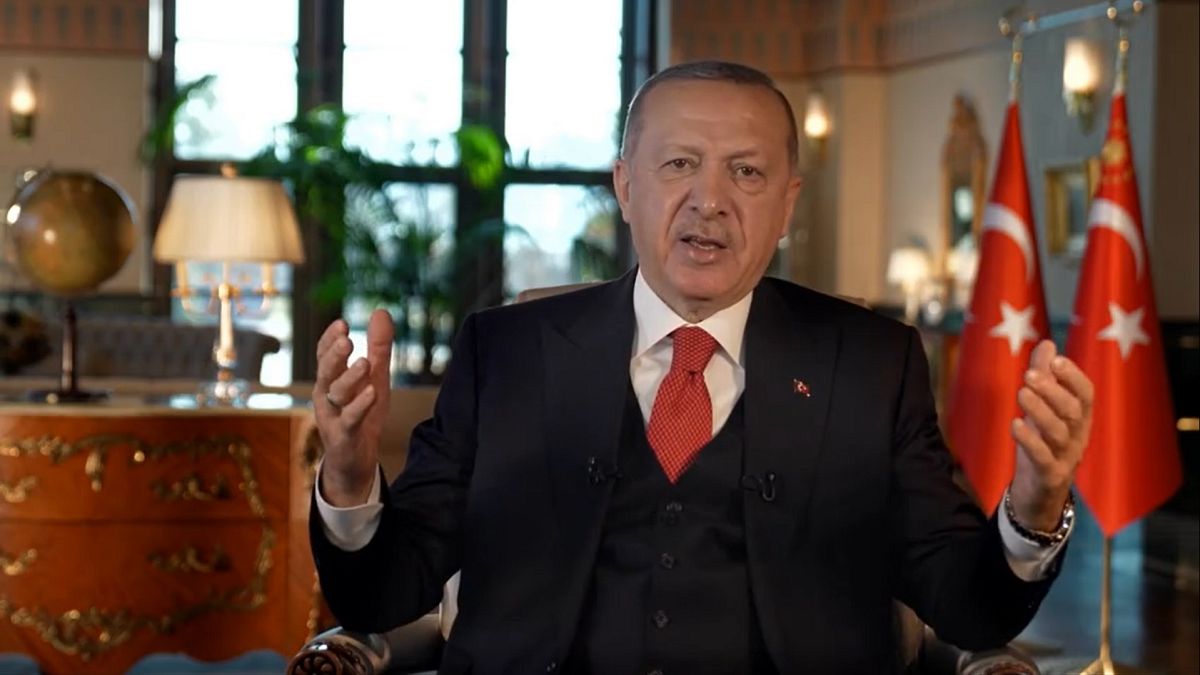

With European sanctions and a possible snap election looming in 2021, Turkey's president says his government is putting the finishing touches on economic and democratic reforms

On the final day of 2020, Turkey’s president promised his people that things will change.

“We are in the process of preparing reforms that will strengthen our economy and raise the standard of our democracy, rights and freedoms,” Recep Tayyip Erdoğan said in the middle of a speech released on the presidency’s website.

“We are making the final adjustments to our comprehensive reform programmes and, God willing, will lay them before the nation with the New Year.”

It is not the first time in recent weeks that Erdoğan has spoken of reform, amid the prospect of European sanctions and speculation of an early election in the summer of 2021.

In November, he said Turkey saw itself “not somewhere else nowhere else but in Europe. We look to build our future together with Europe”.

But after years of being described by European politicians as an autocrat and growing worries of censorship and human rights abuses in the country, the Turkish president's detractors have strong doubts.

Erdoğan might say his proposals are undergoing “final adjustments”, but few outside his inner circle so far know what they contain.

And the president’s often combative language at the end of 2020 — even after he first spoke of reforms — lead many to conclude sweeping change is not likely.

The scale of the task ahead is illustrated by two issues: lengthy detentions before trial, and press freedom.

Mass detentions before trial

A reality that confronts Turkey as it enters 2021 is that hundreds of opponents of the government are still in prison, many having spent years awaiting trial on terrorism charges.

Human Rights Watch says prosecutors in Turkey “regularly open terrorism investigations into people for peacefully exercising rights to freedom of expression, assembly, and association”.

One prominent case is of Selahattin Demirtaş, the charismatic Kurdish politician who stood against Erdoğan in two presidential elections and has been held in prison since 2016.

The Turkish government says Demirtaş stands accused of terrorism relating to incidents dating back a decade.

His supporters retort the accusations are politically motivated.

Last week, Europe’s top human rights court agreed: it ordered Turkey to release him immediately, saying his detention was “stifling pluralism and limiting freedom of political debate”.

But Erdoğan denounced the verdict as “political” and said the European Court of Human Rights was “conflicted within itself”.

He takes a similar view with the case of the prominent philanthropist Osman Kavala, who was on the verge of being released in February when a court acquitted him of organising a series of anti-government protests in Istanbul in 2013, only to be re-arrested hours later for alleged involvement in the 2016 coup attempt.

Waning press freedom

Three events in December alone helped illustrate how much harder it is these days for Turkish journalists to hold their government to account.

On December 23, the exiled reporter Can Dündar was sentenced to 27 years in prison on espionage and terror-related charges for a 2015 story accusing Turkey’s intelligence service of illegally sending weapons to Syria.

Dündar remains in exile in Germany.

Two days later, on Christmas Day, rolling news channel Olay TV announced it was closing down after just 26 days on the air.

Staff said the channel's owner had been pressured by government officials to avoid giving air time to the pro-Kurdish HDP.

Dündar's conviction and Olay TV's closure contrasted with the less-prominent arrest of Ufuk Çeri, a journalist for the news network Medyascope, who was arrested while covering a protest by workers at a bankrupted airline owned by the family of Turkey’s tourism minister.

Çeri says he was held for 24 hours before being released on December 11 without charge.

Fresh elections and sanctions

But there is speculation that the Turkish president’s reform agenda could be a genuine attempt to win back supporters ahead of an early general election in the summer.

Opinion polls suggest Turkey’s economic and political troubles mean that support for Erdoğan's Justice and Development (AK) Party is in long-term decline.

In the past year, a former prime minister and a former economy minister have split away to form movements of their own, eating into the AK Party's traditional, conservative-minded voter base.

Many opposition politicians have sought to unite around the idea of dismantling Turkey's executive presidency system, one of Erdoğan's signature reforms that was narrowly approved in a disputed referendum in 2017.

Another pressure point comes in the form of possible sanctions by the European Union over Turkey's gas exploration in the disputed waters of the eastern Mediterranean.

Greece, Cyprus and France are among the EU members calling for punitive measures — a decision could be taken as early as March.