Since the death of his twin brother in a 2010 plane crash, Kaczynski has been the main force behind the Polish nationalist right. But is his influence beginning to wane?

On 10 April 2010, a Polish military plane went down while attempting to land in thick fog at Smolensk airport in Russia, killing all 95 people on board.

The list of the dead included Poland’s president, Lech Kaczyński, the head of the Polish army, the country’s central bank governor and scores of politicians, offices and historians visiting to mark the anniversary of a massacre of Polish soldiers by Soviet troops in 1940.

Commenting on the crash, the-then Polish prime minister, Donald Tusk, said that it had been the worst tragedy to hit the country since World War II, when the country all but ceased to exist in a vicious Nazi occupation that led the deaths of millions of Poles.

Kaczyński was a divisive politician, a right-winger, nationalist and devout Catholic who was hostile to the European project. He was also an identical twin.

Jaroslaw and Lech Kaczyński were famous even before they rose to the very top of Polish politics. The pair had starred as children in a 1962 movie, Those Who Would Steal the Moon, before becoming activists in the anti-Communist movement as students at Warsaw University.

In the 1980s, both joined the Solidarity movement against Communist rule and after independence in 1989 both were elected to parliament. In 2001, they formed the Law and Justice Party (PiS) which in 2005 won elections, forming a right-wing coalition government.

It was Lech that went for the top job, winning the presidency in 2005. In 2006, he nominated Jaroslaw as prime minister. Whatever people thought of them, the pair had made history as the first brothers to serve as prime minister and president of the country.

It didn’t last long. PiS lost parliamentary elections in 2007 to the pro-European Civic Platform party and Jaroslaw was forced to stand down as PM. Lech, however, remained as president, continuing to serve until his death in the Smolensk crash of 2010.

Lech Kaczyński had been a divisive figure in Polish politics - outspoken, right-wing and happy to use divisive rhetoric to attract support. But of the two brothers, it was Lech that was the more moderate, said Piotr Buras at the European Council on Foreign Relations.

“I think the death of his brother had a very important impact on how [Jaroslaw] went about politics. His brother was a moderating force [...]. He was a counterweight to his radicalism. After his death, Kaczyński was left alone with his radical views,” he said.

In June 2010, Kaczyński ran in a special election to replace his brother. He narrowly lost the first round and then, in a result that shocked many onlookers, he lost in the second.

Kaczyński never again ran for the top job in Polish politics, but his influence and power only grew over the next five years as chief ideologue and strategist of the PiS.

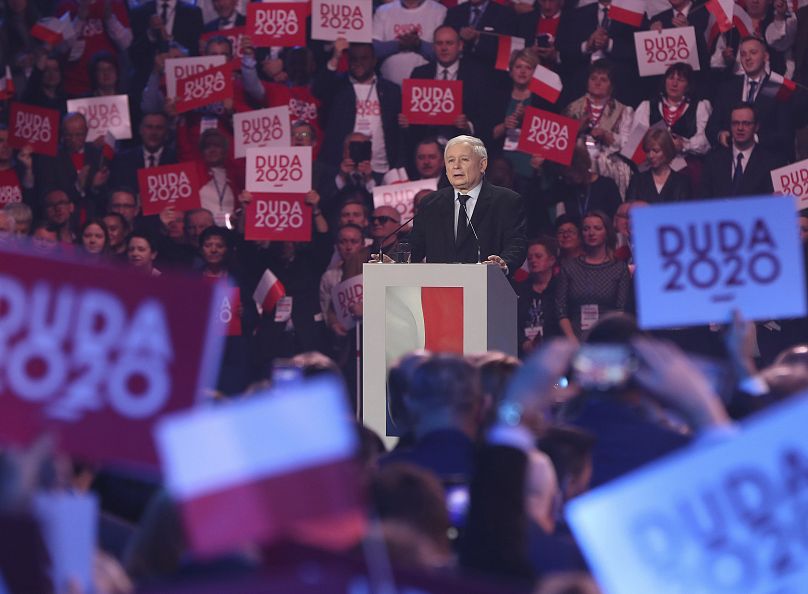

In 2015, PiS swept to power at the centre of a right-wing coalition, United Right, assembled by Kaczyński. Andrzej Duda, hand-picked by Kaczyński, served as president.

PiS - and Kaczyński as puppet-master - has dominated Polish politics ever since, fusing right-wing, anti-EU populism with hostility to progressive elements in Poland such as the LGBT movement, which Duda has attacked in recent days during his election campaign.

The party has ramped up rhetoric against its historical enemies Germany and Russia, using the memory of the brutal Nazi and Soviet occupations to encourage nationalist sentiment.

The mythology of Smolensk

Key to the anti-Russian rhetoric of the PiS has been the mythology of Smolensk, one that posited that the plane crash that killed Lech Kaczyński was no accident, and was instead orchestrated by his enemies in Poland and backed by Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Meanwhile, under the PiS the relationship with Europe has gone from bad to worse, with government efforts to reform the judiciary leading to a legal battle with Brussels.

Through it all, Kaczyński letting Duda and his prime minister, Mateusz Morawiecki, be the public face of the PiS while he remains a backbench MP.

But while Kaczyński’s authority and power in the PiS is unparalleled, it is not absolute.

It was at Kaczyński’s urging that in May, as Poland reeled from the coronavirus pandemic, the government opted to push ahead with the election on May 10 with a postal-only ballot.

Critics argued that not only would such an election be logistically impossible in a country of 38 million people, but it would also pave the way for widespread ballot tampering and trigger the worst crisis for Polish democracy since it joined the EU 16 years ago.

In the face of opposition from within the United Right coalition as well as from outside, Kaczyński was forced to abandon the May 10 election.

“It showed that while Kaczyński’s power in Poland might not be restrained by law, it can be curbed by political realities,” wrote Adam Traczyk and Milan Nič at the Robert Bosch Center at the German Council of Foreign Relations on May 25.

This month’s election could be a second blow for Kaczyński. As he predicted, Duda’s popularity has waned as the economic fallout from the coronavirus pandemic.

Duda is expected not to be able to secure the 50% to win the June 28 election outright, forcing a second round in July, likely against the pro-European Warsaw Mayor Rafal Trzaskowski and his centre-right Civic Platform party.

Meanwhile, Kaczyński, who rarely gives interviews, has suggested that at 70-years-old his time in politics might be coming to an end. Speaking to a gathering of activists in July 2017, said his next term in parliament may be his last: “I’m not getting any younger,” he added.

For Buras, this election is an existential battle for the PiS. If Duda is not re-elected, Kaczyński may not be able to hold together the United Right coalition. Meanwhile, it Kaczyński was to step down as he has suggested, the coalition would be finished, he said.

“The problem with Kaczyński is he doesn’t have any natural successor. He hasn’t nominated anybody [...]. There would be a huge political void in the party [...]”.

“The PiS has already passed its peak. Now the question is: how they will manage the descent? With Duda as president, it is manageable, without Duda it will be very difficult.”