No one before had achieved such a feat, but the succesful flight itself was marred with intense difficulty.

A hundred years ago today — on June 14, 1919 — two aviators successfully took on the groundbreaking challenge to be the first people to fly across the Atlantic Ocean in one continuous flight.

The two challengers, captain John Alcock and navigator Arthur Brown, were experienced fliers, having both served in Britain's Royal Air Force during the First World War.

They rose to the almost 2,000-mile challenge set out by the Daily Mail newspaper, which offered £10,000 (€11,253) in prize money for a successful crossing undertaken in less than 72 hours.

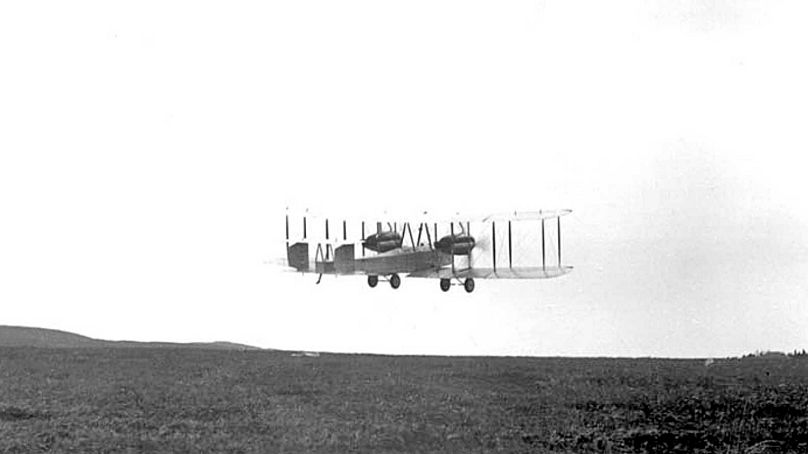

Heading to their starting point in Newfoundland on Canada's east coast, the pair prepared their Vickers Vimy biplane for its venture.

The Vickers Vimy bomber, with its 12-cylinder Rolls Royce engines and wingspan of 67 feet (20.4 metres), was originally manufactured for service in the war, but the war ended before it could see any action.

Alcock and Brown decided to modify the aircraft's design to make it more suitable for their trip by replacing the bomb racks with fuel tanks.

No person or team had ever conducted a nonstop air crossing between North America and the UK and Ireland by 1919.

But the competition was certainly growing.

In the weeks leading up to Alcock and Brown's flight, there were two failed attempts for the prize money.

One was forced to ditch the effort mid-way across the Atlantic, while the second crashed shortly after takeoff.

The first successful flight

The British pair took off from Lester's Field in Newfoundland, Canada, on June 14, 1919, at 6:13 pm CEST, and crash-landed in a bog in County Galway, Ireland, the following morning at 10:40 am.

Their flight time was a little over 16 hours with an average speed of 118 mp/h (193 km/h) for the 1,890-mile (3041 km) trip.

But despite the eventual success, the flight itself was marred with difficulty.

Issues began during take-off as the heavy fuel-laden aircraft struggled to clear the trees, Brown recalled in his later book: Flying the Atlantic in Sixteen Hours.

He wrote: "Several times I held my breath, from fear that our undercarriage would hit a roof or a tree-top."

Then, less than an hour into the trip, the radio broke down and the pair were cut off from the outside world.

Brown's "all well and started" message sent shortly after takeoff was the first and last radio transmission of the flight.

Poor weather then struck.

Alcock recalled in an interview with the Guardian the weather being "very rough and bumpy".

He added: "The wind was blowing hard right down to the water. Five hours from land we endeavoured to get out of the clouds and thick fog, but investigated without avail.”

The continued fog and heavy clouds prevented Brown from keeping track of their location, and it eventually led to Alcock losing control of the plane.

In a near-death call, the bomber stalled and spiralled several thousand feet toward the ocean, which Alcock managed to halt just in time.

He later told the Daily Mail: "I believe we looped the loop and by accident we did a deep spiral. It was very alarming. We had no sense of the horizon."

Just when things couldn't get much worse, the pair were forced to battle sleet and ice that had affected the radiator shutters and covered the petrol gauges from sight.

They were left with no choice but to shut down one of the engines, before moving to a lower, and warmer, altitude to thaw the ice and force a restart.

Less than 30 minutes after doing so, the pair recalled, they spotted land — Ireland.

"We were jolly pleased, I tell you, to see the coast," Alcock said.

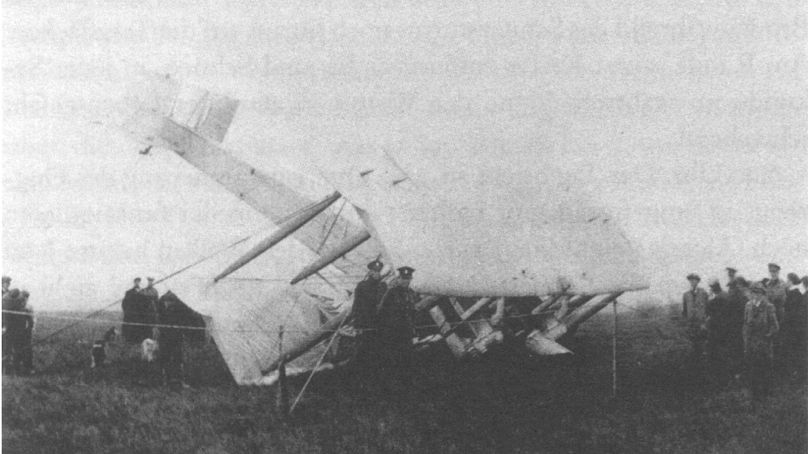

Circling the area, the pair spotted what they believed was a safe landing patch.

But what the pair had thought was a smooth field, was actually Derrigimlagh Bog near Clifden.

They crash landed the Vickers Vimy into the bog, causing the nose to dip, but the pilots — now the first people to cross the Atlantic by air in under 72 continuous hours — were luckily unharmed.

Another, sometimes overlooked, first-time feat was achieved during the trip.

Pointing to a white mailbag containing 800 letters, Alcock told the Guardian: "This is the first Atlantic aerial mail."

The aftermath

Alcock and Brown received not only their £10,000 prize money for the trip, which was awarded by the UK's then aviation minister Winston Churchill, but also widespread recognition.

They were both eventually knighted by King George V.

Alcock died just six months later in a plane crash near Rouen in France. He had been flying a Vickers Viking amphibious aircraft to an exhibition in Paris.

Brown died in 1948 after a period of poor health.