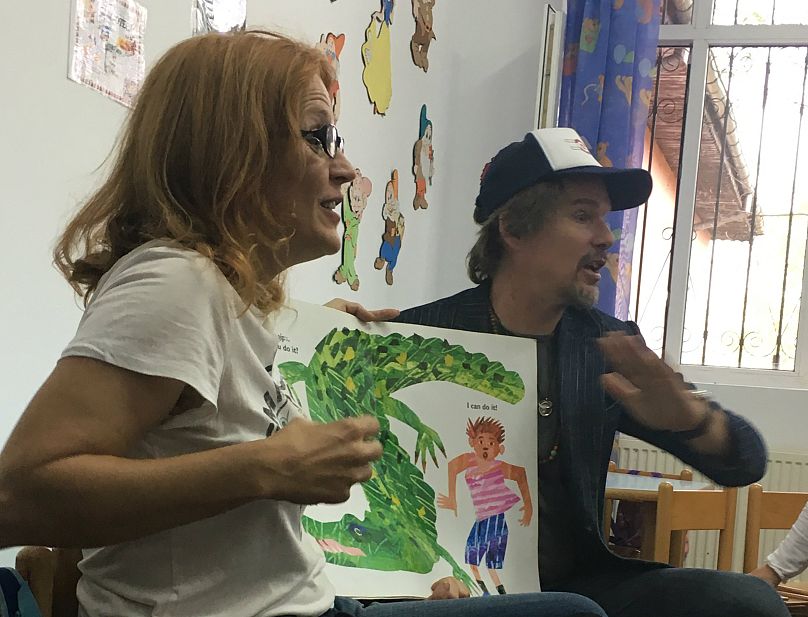

It's hard to say which member of the Hawke family is more famous in Romania: Hollywood actor Ethan or his mother, Leslie, who helped thousands of children attend schools.

It's hard to say which member of the Hawke family is more famous in Romania — Hollywood actor Ethan or his mother, Leslie.

That's because since first travelling to the eastern European country in 2000 as a Peace Corps volunteer, Leslie has, through the OvidiuRo humanitarian foundation she co-founded with Maria Gherghiu, sent thousands of children to school.

'Fretful life'

With a politician as father, Hawke started volunteering early: she has memories of handing out flyers and trying to convince people to vote for John F. Kennedy when she was just eight years old. At the time, she had dreams of becoming a movie star.

Instead, by the time she graduated university at 21, Hawke had given birth to her son, Ethan, and divorced her husband. Her first job, in a shop, was far from the Hollywood glamour she had once aspired to.

Still, Hawke climbed the corporate ladder to become a book editor — but in 2000, she felt she needed a break from her "own fretful life."

"I was making a good living but it all went to maintaining my big city lifestyle — between the Central Park West apartment, the dog-walker, my wardrobe, Sunday brunches and the occasional exotic vacation," she said.

In a major change, she joined the Peace Corps.

It was "the best thing that ever happened" to her, Hawke revealed to Sandra Pralong in "More Romanian than Romanians" — a book compiling testimonies from foreigners living in the eastern European country.

'Hopelessly naive'

That first trip to Romania was a real eye-opener for Hawke, who, accustomed to a luxurious life in New York, was struck to see children openly begging in the street. One of them was Alex, an 8-year-old boy begging barefoot in the middle of traffic in Bacau, a city in the east of the country.

For two days she observed passers-by ignoring the child as if he was invisible until on the third day, she finally worked up the nerve to introduce herself.

He told her he was orphaned.

But she soon discovered that was far fom the truth when his mother turned up at the shelter Hawke had taken Alex to, irritated that Hawke had broken "the economic chain" of the family.

Begging is illegal in Romania but authorities often ignored the problem partly because of a local self-defeating "asta este" (that's it) mentality, and partly because as policemen asked Hawke: "Which would you prefer they do — steal or starve?"

Undeterred by local officials who branded her American attitude "hopelessly naive", Hawke joined forces with Romanian teacher Maria Gheorghiu.

Together they launched their foundation in 2004 as well as a training programme for mothers and children, inspired by Alex.

'Not making a long-term difference'

Through the programme, mothers were supposed to receive money provided their children went to school every day. The idea was based on a similar project for homeless men Hawke was familiar with in New York.

"Originally what I wanted to do was help some kids on the streets in Bacau into school," she told Euronews.

"And then we wanted to get the authorities and the general public to understand how important it is to educate all of Romania's children — and not just turn a blind eye to the situation," she added.

But as the children grew older, Hawke and Gheorghiu saw that sending them to school was not enough — the initial "success stories" had instead turned into quiet tragedies. Alex had dropped out of school in the hope of finding a better life in Italy, while another girl had gotten married in her teens.

"We couldn't ignore the evidence. We weren't making a long-term difference," she said.

Functional illiteracy

According to Eurostat data, Romania tops the EU ranking for functional illiteracy — whereby reading and writing skills are inedequate to manage daily living and employment tasks that require reading skills beyond a basic level — with 40% of pupils unable to understand a text upon first reading.

The percentage of school drop-outs is also significantly higher than the EU average.

Hawke and Gheorghiu found that the younger siblings of the children they'd helped, who started school at 4 or 5 years old, were faring much better.

They therefore decided to eradicate the problem at the root, by providing help early in childhood, before children made it onto the streets.

Their flagship "Fiecare copil in gradinita" (Each child in kindergardden) programme was launched in 2010 to provide education to the poorest, most marginalised children.

Parents who send their children to kindergarden receive a 50 lei (€11) social ticket at the end of each month to buy food, sanitary products or material for school.

In 2016, the programme was taken over by the state, which now pays the social ticket to families whose monthly income is lower than 284 lei (€61).

Still, according to OvidiuRo statistics, while over 110,000 children aged between 3 and 6 years old are currently living in poverty in Romania, only 60,000 were enrolled to receive support to attend kindergarden in 2017.

'Ability to adapt'

"If you want them to stay in school until they have marketable skills, if you want to lower the school dropout rate, you have to provide quality early education," Hawke stressed.

"After-school and second-chance programmes, by themselves, are too little too late. When combined with quality early education, they do work in helping disadvantaged children succeed in school," she added.

Children benefitting from the programme will be monitored until 2020 in order to get a generational scope on the results. Hawke then plans to leave Romania to return to her native US.

But she is positive about her adoptive country's potential for change.

"Romania's problems are serious but they are on a relatively small scale and on a entirely corrigible scale," she told Euronews.

"Romania has formidable resources and a legendary ability to adapt at times," she said.