The Asian Civilisations Museum in Singapore has decided to unveil this extraordinary story with its latest exhibit — and in an interview with Euronews.

If somebody says "Angkor", most of the people think of a grandiose complex of strange ruins somewhere in Asia, partly hidden in the jungle. But Angkor, a UNESCO World Heritage site, is much more than that. It is widely considered to be among the world's most magnificent architectural masterpieces — its extensive complexes and detailed stone carvings have intrigued innumerable travellers, scientists, historians, and archaeologists. It has an adventurous and animated "modern" history as well — even if not so many people know of it.

The Asian Civilisations Museum in Singapore has decided to unveil this extraordinary story to the larger public as well Euronews, which interviewed with one of the curators, Stephen Murphy, who specialises in the art and archaeology of early Buddhism in Southeast Asia.

Euronews: Why and how did you decide to organise this exhibition?

Stephen Murphy: This special exhibition is a collaboration with the French Guimet Museum. There is a 10-year agreement between Singapore and France and, as the Guimet Museum are actually renovating their galleries, we were able to borrow their collection. We were really lucky because normally they don't lend it to others. And we couldn't say no, especially because it was just like we won the jackpot!

Euronews: Why is it such a big deal?

SM: Angkor is one of the few archaeological complexes that can be seen even from space, because it's so big. It covers about 1,000 square km. But usually shows on Angkor focus just on the civilisations itself, not its history or the remaining artefacts we have, and what dates, sometimes, as far as back as the 6th century.

Our show has two parts. The first part says how the French discovered, or rather "rediscovered", and reintroduced the city to the Western world. You cannot disassociate the French with Angkor, it's impossible, their history is absolutely interwoven with Angkor.

In 1863, a French naturalist called Henri Mouhot gets taken to the temple. He wasn't the first one, because 15-16th century Portuguese and Spanish also knew about the place, and even a French missionary visited the temple before him, but he was the first who made an account of it. Unfortunately, Mouhot died, probably of malaria, before he could do anything with his discovery. But one of his servants collected his diaries and published them posthumously.

It caused a sensation, called the Lost Civilisation. Then several years later, another French mission went there, basically to navigate the Mekong River through China, searching new trade routes and they arrived at Angkor.

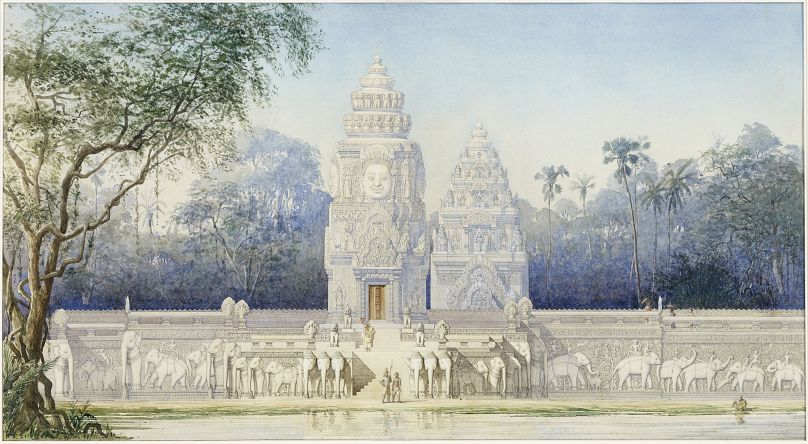

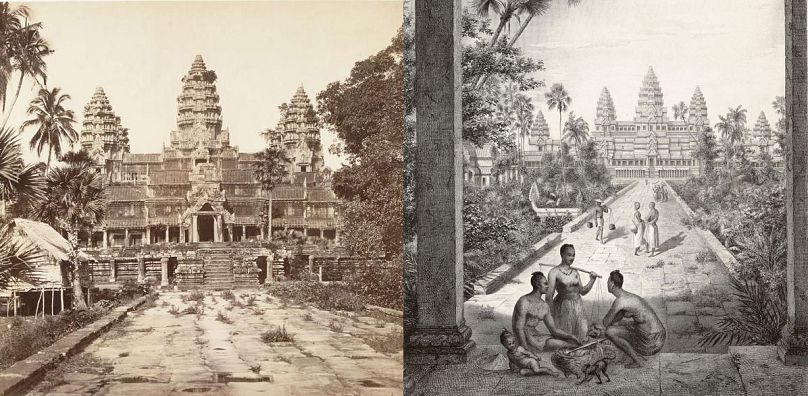

The way they presented Angkor in their drawings, watercolours and wood engravings was romanticised and more exotic than the reality itself. As they couldn't publish photographs to the wider public yet, they made Orientalised lithographs about it. One of the strong points of the exhibition which made pairs of the photos made at that time about the actual buildings and their counterparts on the drawings. A good example of this is the watercolour painting of the elephant terrasse, which is accurate but very orientalised in the same time: it was "fixed" in a certain way, adding details that never existed to make it more attractive. (picture is above)

Euronews: Why did they do it? Did they make the lithographs more attractive to sell books?

SM: No, not really. On the one hand, people like Delaporte (a member of the mission) had a genuine intention to make made everything more authentic — and of course, they had to justify the funding received to do the research and to convince people it was worth giving money to future expeditions.

And than Angkor went to France — literally. Delaporte went to Angkor twice yet, once in 1873 and then in 1881, when he had permission from the king of Cambodia to collect 70 sculptures from Angkor. The idea was that all these are going to the Louvre, but obviously, they couldn't move the whole temple to France, so they made plastic casts of the walls. The interesting thing is that when he finally brought these 70 plastics and statues to France, and the director of the fine arts gallery of the Louvre opened the crates, he said: "No way! I don't know what it is, but it won't ever go in the Louvre!"

When people first saw it, they didn't really have an eye for it, they thought it was crude because it was so different from anything they've seen until then. So they set up a museum 18 miles away, kicking them out into the suburbs to the Chateau de Compiègne just like an exile. Delaporte tried everything, but it was in vain, nobody visited the exhibition.

Euronews: What happened next?

SM: Luckily, in 1931, a colonial exhibition was organised in Paris, in the Palais of Trocadero, where they showed part of their exhibition: they created an almost life-size version of Angkor in Paris from the plastic casts.

It was very well illustrated with photos, journals at that time can be seen as part of our expo. But it was also very political and propagandistic to justify why they colonised, why they "civilised" or "saved" the civilisation of Angkor. There was always a political aspect behind it, to justify French colonisations. This period, when they started to lose their colonies, it was an extremely crucial point to prove it.

Euronews: What are the most interesting parts of the exhibition?

SM: In the second section of the collection, we see all the amazing sculptures we left from Angkor in chronological order. Everything is original here. One of the most interesting stories is concerning a female statue, a goddess. The body was in the Guimet Museum since the 1930s, but she had no head, it was just a torso. Nobody knew that the body had a head because they were separated so long ago. In 2006, the American ambassador to Cambodia had been given a gift by the Cambodian government, which was a stone-curved head. Later, he gave it to the Guimet Museum as a gift. And sometime after, when the Guimet curator was in the gallery, he suddenly realised it's a match! When he tried (putting them together), it clicked perfectly. He had maybe one in a million chance for this — but it happened.

Euronews: Do you have a favourite piece?

SM: I love the pieces at the start because they are the finest pieces of the 7th-8th century. Amazingly preserved during so many centuries that every little detail could be seen even today.

Euronews: Why is this exhibit a must-see for visitors to Singapore?

SM: If you've never been to Angkor, it's a really great introduction, because you will see the whole picture of how Angkor became so important and so popular today. If you've been there, you still can learn a lot from the site. It's a one-time opportunity, so I encourage everybody to come and benefit from it.

The Angkor: Exploring Cambodia's Sacred City -_ Masterpieces of the Musée national des arts asiatiques - Guimet__ is open from 8 April - 22 July in Singapore._

**Photo credits:**Musée national des arts asiatiques - Guimet