Black journalists put themselves on the dangerous front lines of the US civil rights movement so the sacrifices of activists would not go unnoticed.

As a journalist for the black press and later for The Washington Post, I covered two seminal events of the US civil rights movement that helped prompt passage of the public accommodations and the voting rights acts — the most important pieces of legislation of the 20th century.

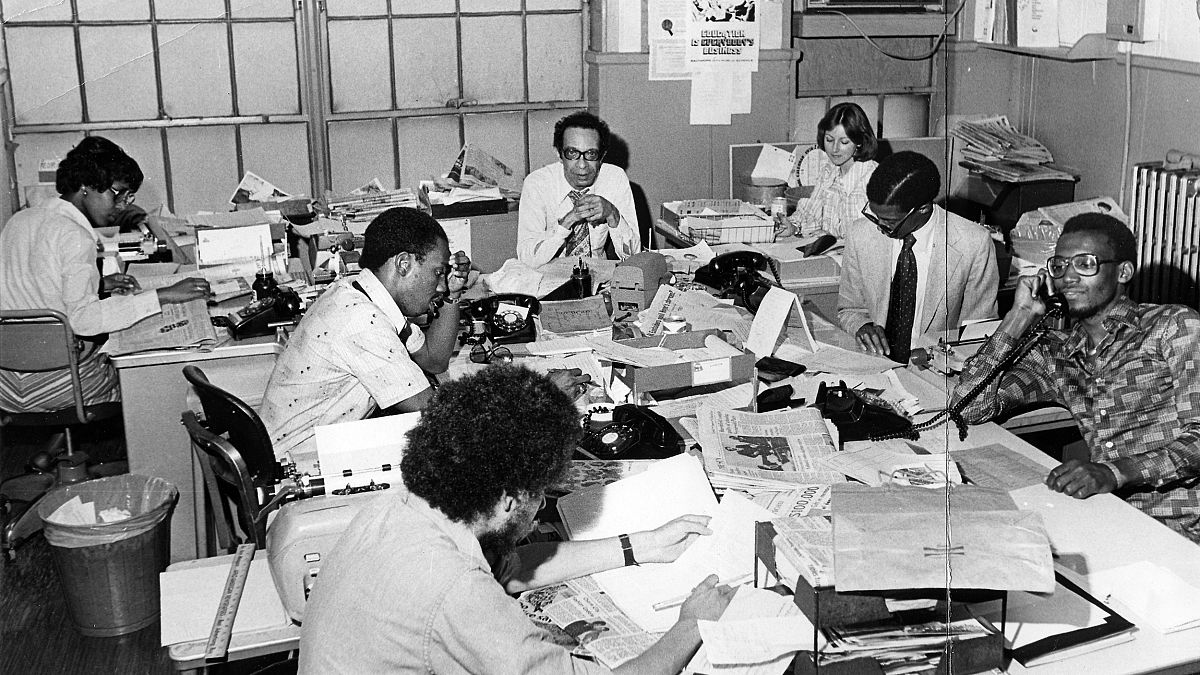

The critical role of the black press in the civil rights movement has not received the attention it deserves. Black journalists put themselves on the front lines of these stories before and during the civil rights movement, doing the work and putting their bodies in danger so the sacrifices of activists would not go unnoticed. The nation needs to acknowledge and learn from the experiences of those who witnessed those early civil rights protests if we are to actualize Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.'s dream.

I grew up in the segregated American South, where I faced humiliation and rejection with "white" and "colored" water fountains and toilets. But I also was in a rare situation — both of my parents graduated from black institutions of higher education. Many young black people like me learned education would be the key to help us overcome racial discrimination. Our families, churches, teachers and communities worked hard to prepare us to succeed in spite of the harshness of segregation.

Many young black people like me learned education would be the key to help us overcome racial discrimination.

But education wasn't an all-access pass. When I graduated from Lincoln University in 1957 at the age of 20, I tried to get a job at a white daily newspaper but none would hire me. Daily newspapers and television were rigidly segregated.

So instead I went to work for the Tri-State Defender, a black weekly newspaper in Memphis, Tennessee. L. Alex Wilson was the editor, a veteran of reporting in the South and highly respected by the small band of black reporters from other outlets with whom he shared this highly dangerous beat. This band included Clotyle Murdock of Ebony Magazine, Francis H. Mitchell and Mark Crawford of Jet Magazine, Simeon Booker and Larry Still of Jet's Washington bureau and others.

In September 1957, Mr. Wilson headed to Little Rock, Arkansas to cover the Central High School integration — an event which had been carefully planned and was expected to go smoothly. Instead it became a showdown over states' rights.

"It's too dangerous there for a girl." Wilson warned me as he left Memphis. It turned out to be dangerous for him, too. Wilson was part of a group of African-American reporters who were attacked by about 50 white men.

“It’s too dangerous there for a girl.” Wilson warned me as he left Memphis. It turned out to be dangerous for him, too.

I watched the attack on the small television in our Beale Street office during the evening news. I could not believe that people all over the nation and abroad were watching my dignified boss being pummeled, shoved, slapped and taunted by a mob. And through it all, he refused to run. They kicked him and he still refused to run even as a brick hit him directly on the back of the head.

I was spurred to action. I called freelance photographer Ernest Withers and said: "Let's go to Little Rock this evening." We drove directly to the home of LC and Daisy Bates, leaders of the local NAACP who also ran an influential newspaper.

"Why'd you bring that girl over here?" Wilson barked weakly. The photographer looked squarely at me and then at my boss. "It was her idea," he said. The next day I covered the arrival of troops that President Dwight Eisenhower had reluctantly sent in. It was from those veteran journalists that I learned it would take courage if I were to make a difference as a journalist.

Reporters risked their own safety to slip in and out of the South to tell of the brutality, lynching and fears that ruled there.

Black reporters played a crucial role in the years before and during the height of the civil rights movement. Reporters risked their own safety to slip in and out of the South to tell of the brutality, lynching and fears that ruled there. Black leaders like Dr. King knew the media was needed to get the message out and I was privileged to become part of this important community.

Fast forward to 1961, when after graduating from the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism, I was hired as the first African-American woman reporter at the Washington Post. My most memorable early assignment was when city editor Ben Gilbert selected me to help cover the integration of the University of Mississippi in 1962. While I was anxious to have a part in such a big civil rights story, I was definitely nervous about going to Mississippi.

Black life in Mississippi at that time was considered cheap. A culture of unrestrained violence against blacks flourished and nearly half its citizens still could not vote.

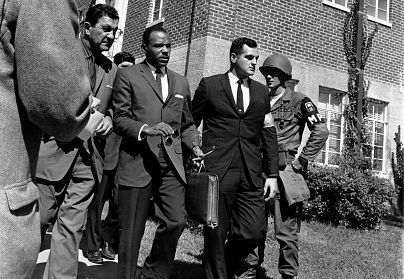

But one brave man decided to risk death to change the laws. His name was James Meredith. In 1962, Meredith and his federal government escorts finally got onto the University of Mississippi campus on the third try, fomenting a riot in which two persons were killed.

Most of the black reporters and photographers couldn't find a way onto the campus in Oxford, Mississippi for fear of death. But once Meredith registered with school officials and the troops were in place we were finally able to report from the campus.

I spent those nights sleeping in a black funeral home because there was no hotel that would allow black people to rent a room. The first story I wrote was headlined "Mississippi Negroes happily stunned by Meredith" — it appeared on the front page of the Post on Oct. 6, 1962.

I also interviewed Medgar Evers, the NAACP field secretary in Mississippi, who outlined the steps he said would be taken to get other blacks to apply to other state schools. Eight months after our interview, Evers was assassinated outside his home on June 12, l963. He was 37 years old — a heroic martyr to the cause of freedom.

Americans must remember just how much blood was shed so that things like school integration could become a reality. And yet, so much inequality remains.

Nearly 60 years later, Americans must remember just how much blood was shed so that things like school integration could become a reality. And yet, so much inequality remains.

Toward the end of his life, Dr. King stated, "the curse of poverty has no justification in our age. It is socially as cruel and blind as the practice of cannibalism at the dawn of civilization, when men ate each other because they had not yet learned to take food from the soil or to consume the abundant animal life around them. The time has come for us to civilize ourselves by the total, direct and immediate abolition of poverty."

Dr. King would be horrified if he could see the decreased standard of living so many women and children experience today. He would have been deeply disappointed that the problem of poverty has increased in practically every major city in the nation, and that the rich are getting richer while the poor are getting poorer. For years, the black press has worked to keep the stories of inequality and injustice alive. Today, the media has become (slightly) more diverse but not nearly enough. Journalists have an incredibly important role to play in the continuing struggle for equal rights. This is fact — not fake — news.

Dorothy Butler Gilliam is a former reporter, editor, columnist and the founder of the Young Journalists Development Program for The Washington Post. She served as the Shapiro fellow at The George Washington University's School of Media and Public Affairs from 2003 to 2013. "Trailblazer" (Center Street Imprint), her memoir, will be published in January 2019.