As the Syrian war marks seven years on March 15 — a peaceful resolution is far from reach as the siege on Eastern Ghouta continues. Euronews speaks with Syrian refugees and asylum seekers in Europe on if they plan to return home.

Seven years have passed since the conflict in Syria began, leaving a legacy of death and displacement in its wake.

The labyrinthine conflict has splintered the nation, with government loyalists, rebel militants, extremists and foreign fighters waging campaigns across the length and breadth of the country.

Observers say the human cost of the war has few modern equivalents.

An estimated half a million Syrians have been killed and 6.1 million internally displaced, according to the United Nations.

From years-long city sieges to the destruction of historic landmarks, much of the country’s infrastructure has been reduced to rubble.

Millions of Syrians have sought safety in neighbouring countries, or made the perilous crossing over the Mediterranean in search of refuge in Europe.

From the global actors deploying ground troops and bombers, to the states housing those displaced, little of the world has been untouched by Syria’s war.

The conflict in Syria began in 2011, amid the Arab Spring protests against autocratic regimes that had swept much of the region.

On March 15, thousands of people gathered in cities across Syria to oppose the regime of Bashar al-Assad in what activists dubbed the “Day of Rage”. The crowds were violently dispersed and demonstrators arrested.

Three days later, on the “Day of Dignity”, protests continued across Syria’s major cities and in Dara’a, the so-called cradle of the revolution, where four demonstrators were killed by security forces.

Despite the violence, the protests continued to grow.

Related: View | How sectarianism can help explain the Syrian war

“The sheer emotion and what it meant on a human, personal level for people to protest is something that has floored me,” Wendy Pearlman, a professor at Northwestern University specialising in Middle Eastern politics, told Euronews.

In interviews Pearlman conducted with scores of Syrian refugees in Lebanon, Turkey, Jordan and Europe between 2012 and 2017, she says the memories of the early days were of euphoria.

They say “‘it was the greatest moment of my life,’ ‘it was the first time I breathed,’ ‘it was the first time I felt like a Syrian citizen,’” she said.

But, she added, as the war has continued to escalate, people have become more reluctant to recall those memories.

“For a lot of people now, it's really painful to recall those days, even the times of total euphoria and liberation and joy. It’s all the more painful to even think about that now in relationship to the hopelessness that so many people feel.”

Mapping the future

In interviews Euronews conducted with several refugees living across Europe, many said the early days of the uprising had proved the most defining of their lives.

Omar Alshgore was still at school when the conflict began. He attended protests in his hometown of Baniyas without any real understanding of what he was fighting for or against.

“I was 15 years old and didn’t know what it means — freedom or police,” he said. “I know that in our schools, they taught us that police are people who save your lives but when I was there I saw them kill my friends, and arrest me and torture me.”

Omar was imprisoned several times for a period of days for attending the protests, before finally being imprisoned for three years.

During his incarceration, he says he endured torture on a daily basis. He later learned that a security officer had told his mother he had died, while he spent much of his time behind bars believing his family had all been killed.

“When I came out of prison I was 20 and a half years old. I was sick with tuberculosis and weighed 34 kilograms,” he said.

“My mother couldn’t remember me when she saw me... She could just imagine a beautiful child, not me as a horrible person.”

His mother, who had paid for Omar’s release after being informed that he was still alive, sent him to Greece in search of medical care.

Unable to get the assistance he was looking for, he says he travelled through Macedonia, Serbia, Croatia, Slovenia, Austria, Germany and Denmark before eventually settling in Sweden.

Now re-doing his final year of high school, and with more friends than he has time to see, Omar says his experience in prison helped him make the move to Europe.

“When you go from hell to heaven it’s so easy,” he said.

The war in Syria has forced millions of people like Omar from their homes.

While the majority have fled to countries neighbouring Syria, around 1 million have sought asylum in Europe, according to official figures.

“It’s one of the biggest, single most important refugee crises in the 21st century,” UNHCR Assistant High Commissioner for Protection Volker Turk told Euronews.

The war has “dissected the whole social fabric of a society. That’s enormous for a population that is known to be very educated, to be extremely innovative and creative. And to see this ruin in front of our eyes is heart-wrenching,” he said.

Refugees interviewed by Euronews said they travelled to Europe to flee imprisonment and death, and in the hope of building a new life away from the destruction that had besieged their homes.

But the journey itself was far from easy.

The International Organization for Migration (IOM) says the Mediterranean crossing is “by far the world’s deadliest” journey for migrants, with at least 33,761 people reported to have died or gone missing between 2000 and 2017.

Manal and her children are among those to have boarded a boat to Europe.

Then working for the Syrian Ministry of Justice, Manal fled Syria in late 2014 following direct threats to her life by militants.

However, a lack of funds and time forced her to leave her three children behind.

After making it to Denmark, Manal was devastated to learn that she would have to wait for three years to obtain the right for her family to join her.

Unwilling to do so, she turned to the smugglers who had facilitated her crossing and paid for her three children, now aged 18, 14 and 9, to make the journey the following year.

She kept in touch with her eldest daughter via Whatsapp but became concerned when the messages stopped.

“Hours later I read the boat is broken [and] a lot of people have died. I don’t know what happened with my kids,” she recalled.

“I need to know about my kids — if they’re dead I need to know where are the bodies, if they’re alive, I need to know.”

For days, Manal scoured through photos of dead bodies, searching for her children until, as she was beginning to lose all hope, a message arrived on the ninth day from a stranger on Facebook telling her that they were alive.

“Believe me, all nine days I don’t know about them, in the morning and evening, I stopped eating. I lost weight. I became crazy,” she said.

Now reunited in Denmark, Manal says the family are trying to forget the horrors of the voyage.

“My son is treated by a psychological doctor. Seven years old he sees people shouting, dying in front of him,” she said.

“We’ve had a very hard time and this has affected our psychological [health]... I’m broken, I’m shattered. But I need to be a very strong women because I have kids.”

A new life?

Like Manal and her children, for many Syrian migrants the difficulties don’t end when they reach Europe.

“In Europe, asylum seekers are consumed with the difficulty of starting life anew, of learning languages, dealing with bureaucracy, getting job re-training, figuring out if they’re going to be able to work in the profession they had back home,” explains Pearlman.

“Their lives are in this limbo which emotionally absolutely takes a really hard toll.”

Issues of starting life anew in Europe are no clearer than in Greece’s overcrowded refugee camps.

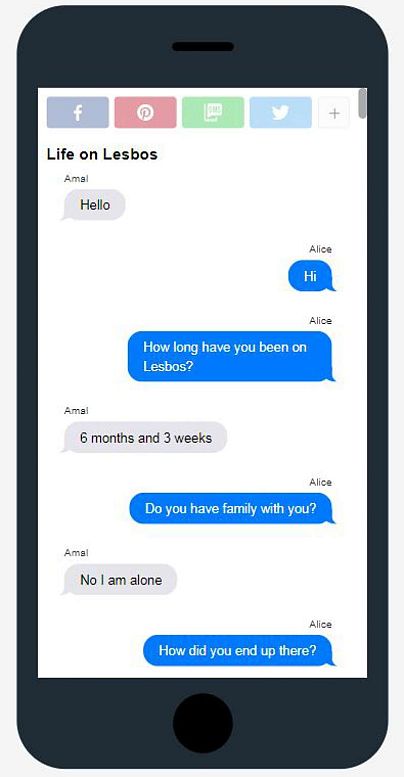

Amal Adwan, 47, says she decided to leave her home in Damascus and travel to Europe because the “war and death everywhere” had rendered her a stranger in her own country.

When she boarded the boat to Europe, Amal recalls thinking “if I die it is my fate and if I reach Greece my life will be better.”

However, while life in Lesbos’ Moria Camp saved her from bullets and bombs, it was far from a blissful haven.

Amal and other asylum seekers Euronews has spoken to describe a pervasive feeling of hopelessness in the camp that has bred crime, alcohol dependency and drug addiction.

“People shouldn't stay in Moria more than one or two weeks. It is not for human[s],” she said.

Now living outside of the camp and awaiting approval on her asylum application, the former medical statistician hopes to find a job in Greece.

Turk of UNHCR said Europe and the rest of the world must find ways of investing in Syrian migrants like Amal so that “they can get on with their lives.”

“We need to have and show continued compassion and solidarity with refugees outside; both in neighbouring countries and elsewhere,” he said.

But, he warned, “We also see their decline in coping mechanisms, because for them this has been much too long - it’s one of the most protracted crises of that magnitude that we have seen.

“It will require a lot of work.”

Return home?

Many of the asylum seekers and refugees Euronews spoke to said they dreamed of returning to Syria.

“I hope the situation will improve, we want to go back to our homeland, our country. There is no place like home, in spite of everything,” 38-year-old Rasha, an asylum seeker at Moria camp, said through tears.

But seven years after the conflict, observers warn that there is still no end in sight.

In 2018 alone, there have been record levels of displacement, increased civilian casualties, rising attacks on education facilities and a systematic denial of aid, NGO Save the Children warns.

Turk says it is not the time to facilitate or promote returns to Syria.

“It’s absolutely clear that we need an end to violence inside Syria,” he said. “We need a political solution.”

As bombs continue to fall in Ghouta and elsewhere in the country, refugees like Omar are now focusing on making the most of their new lives.

“I want to tell Europe that we can make a difference — we are very good people, we are from a very good country; we are here because of the war which started for political reasons,” he said.

“I hope it [the war] will finish soon, but it’s a big war, not only for Syria but for the world. The world is fighting there. The Syrian people have to make the solution.”

Additional reporting by Sallyann Nicholls