Last year’s United Nations Climate Conference in Bonn – the COP23 – provided a stark warning to what will happen if we do nothing to stem the rise of the planet’s temperature. As the ice caps melt and water levels go up, large areas along the coast may soon face a salty fate, especially in the Netherlands, Belgium and Greece. Sea levels are expected to rise between 40 centimetres and a full metre by 2100, according to the latest projections from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

Preventing the damage may be possible, but it will be extremely expensive. A World Bank report released during COP23 showed that Fiji, an early victim of the global trend, is facing a $4.5 billion bill over the next decade to keep ahead of the damage of rising sea levels. This number is equal to Fiji’s entire GDP. As the water is not rising at an even level around the globe, the situation in Fiji is a warning to Europe and other parts of the world of what lies ahead.

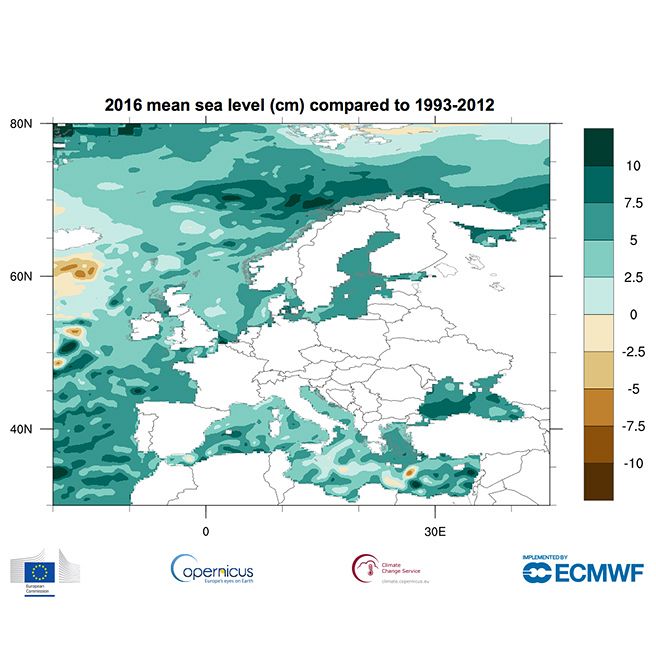

Sea levels have been rising 3 millimetres every year since 1993, according to the European Environment Agency, meaning the world’s oceans are now more than 7 centimetres higher than they were 25 years ago. Considering that sea levels have risen a total of 19.5 centimetres over the past century, the increase has not happened gradually – in fact the problem is rapidly getting worse.

Exactly to what extent the oceans will rise will depend on our efforts to curb global warming. While most of Europe still has time to prepare for the flood, for many cities this is not a problem for the future – danger is already knocking at the door.

The city of Venice is working on installing 57 flood barriers to stop the sea from flooding into the lagoon, spending €5.5 billion to protect the historic site. The Netherlands, veterans at flood management, have responded to the problem in part by designing houses that float. In Britain, £1.8 billion has been earmarked to defend London and the areas around the Thames from flooding over the next century, as the south of England regularly suffers damage in winter floods. Barcelona, Istanbul and Dublin, as well as large swathes of the Netherlands and Belgium, are also vulnerable to rising waters.

This means politicians and policymakers across Europe need to act now to prevent catastrophic damage. The approach is two-pronged: installing physical measures to protect areas from water damage, and equally importantly, working on reducing the damage to the environment that causes the sea levels to rise while there is still time. Both these efforts require detailed and reliable information about how the coastline may change in each local area.

The Copernicus Programme provides vital data and information on mitigating climate challenges. “Monitoring sea levels is key to tracking the evolution of our climate,” says Jean-Noël Thépaut, Head of the Copernicus Climate Change Service. “It is important that authorities and policy makers have a holistic view of the climate change challenge, and how it affects many aspects of the planet.” This is why Copernicus Climate Change Service not only monitors sea levels, but also sea ice, sea surface temperature, and land variables like soil moisture. “We want to have an integrated approach to what we call the water cycle, as this lets us track the evolution of the climate as a whole.”

One of the organisations providing data to the Copernicus Climate Change Service is CLS, the French research institute for sea exploration. Gilles Larnicol, Head of Oceanography at CLS, says a key role of the organisation is to ensure the data collected is accurate and beyond reproach, so decisions can reliably be made on the back of this analysis. “Whenever a new harbour or a building is placed close to the coast, the construction has to consider the projected sea level rise,” says Larnicol. “The IPCC model is central to this, but it is important to cross-check the information with other sources, such as the data that we collect.”

Future infrastructure construction will have to take into account the projected sea level rise

In recognition of the importance of sea levels as a global warming indicator, last year’s United Nations Climate Conference dedicated two whole days to the ocean. 194 countries have signed the Paris Agreement, which aims to limit the increase of the planet’s temperature to 1.5-2°C by the end of the century. Jean-Noël Thépaut, Head of Copernicus believes there are causes for optimism: “The target is challenging, but if countries commit to working towards these goals by acting on reducing greenhouse gases emissions, it will be possible to limit the effects of climate change, confine temperature increases to acceptable levels, as well as consequently holding back the rising sea levels.”