French journalist Samuel Gratacap went to one of the hottest spots for human trafficking. to learn what people there have been through

“We were being pestered, they were taking drugs, beating us. You are in the house, in the cell and suddenly someone jumps on you. You are in the shower, someone comes, opens the door to force us out.”

This is a testimony of Mireille, as told by French journalist Samuel Gratacap. He met Mireille in Libya and recorded the story of her forced stay and then escape from the detention centre for female migrants in Sorman. She was taken to prison after her arrival to the city with her aunt. She says she planned to stay Libya, not to cross Mediterranean to reach Europe.

“I don’t know if people there were intending to get a boat but we only heard here, in Libya, that there was a possibility to go to Italy. The rest of us, we didn’t know, when the police took us, they thought we were getting a boat but we weren’t. We came to stay and find a job,” she added. “The policeman tells us we want to leave to Italy. I say: ‘No’.”

The town of Sorman is located between the Tunisian border and Tripoli. The detention centre there takes illegal women migrants, mostly from sub-Saharan Africa, who arrive there in transit. They say they have to put their lives in the hands of smugglers, who steal their property and abuse them.

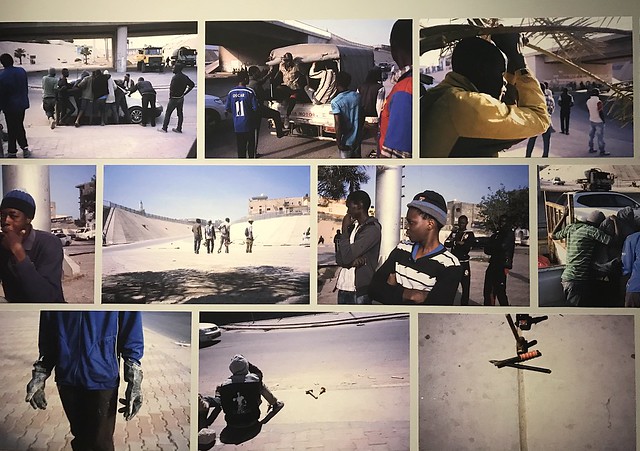

Gratacap collected these stories of human suffering while travelling in Libya, along the Tripoli coast, over the last three years. Among the cities he visited were the iconic locations where the Libyan revolution unfolded in 2011 – Misrata, Sirte, Tripoli.

It is all the subject of an exhibition in the French city of Arles this summer, called FIFTY FIFTY.

The title refers to migrants’ predicament once they had arrived in Libya and after the revolution. Some had come from other African countries to search for jobs; others looked to travel to Italy. But all of them were caught in the chaos, between life and death; they could neither advance nor return.

The journalist has collected dozens of stories and presents them in photographs, audio and videos from Libyan ports, detention centres, prisons, workers’ waiting zones and construction sites.

An inmate at a detention centre for migrants in Zawiya told him: “They are beating us here every morning, every evening. We don’t eat, we catch diseases, there are lots of diseases here. Our relatives, our families don’t know where we are. It’s been more than six months, seven months now. They don’t know if we are dead or still alive. They tell Europeans that they caught us on the sea and that’s not true. They are selling us. They are running the prison and organising the departures for Italy.”

“The only way of escape the prison is to pay, thereby becoming tied into a debt system. This is the point of no return. The only way to leave it is to pay again, by prostituting yourself or working for free. And you find yourself dragged once more into another spiral. From then on, immigration is no longer a choice, it becomes imperative as the only possibility to move forward,” – said the journalist explaining what he witnessed in Libya.

In January 2016, Gradacap met Libyan amateur photographer Mansour who remembers the time he witnessed the capsizing of a smuggler’s boat. The wreckage was washed back ashore by the sea, packed with the bodies of drowned migrants; other corpses continued to return to the beach all through the following week.

Mansour says he no longer has the strength to look at the pictures he took at that time, nor can he delete them from his computer. His only hope is that one day fishermen and the children who accompany them will be able to walk in the shallows waters without the risk of stumbling upon a drowned body:

“Everyone was talking about the tragedy that happened on the boat, even children were talking about this. Instead of thinking about the good times at the beach. I know people who do not come to the beach anymore, because of what they saw. They can’t eat the fish anymore because of this.”

In the first 7 months of 2017 more than 114,000 migrants and refugees entered Europe by sea, according to the UN . Almost 85 per cent of them arrived in Italy via the main Mediterranean route linking the country to Libya. More than two thousand asylum seekers have drowned over the same period of time.