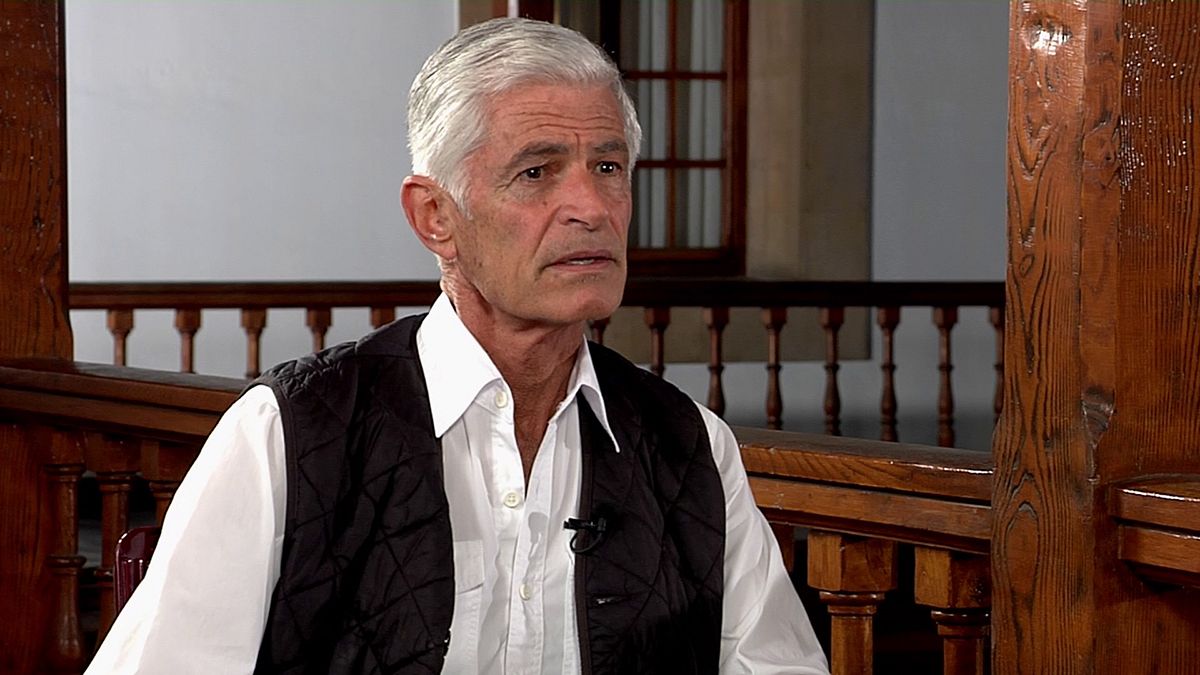

*James Nachtwey is one of the greatest photographers of our time.

*James Nachtwey is one of the greatest photographers of our time. For almost four decades he has been observing suffering face to face, documenting poverty, famine, disease and conflicts. He decided to become a war photographer after watching the images from Vietnam taken by reporters such as Don McCullin, mainly because of the power of those pictures to incite people to revolt against war. Despite spending almost all his career in war zones, he presents himself as an anti-war photographer and he still believes in the power of images to prevent conflicts. He has just been awarded the Princess of Asturias Award for Communication and Humanities.*

*James Nachtwey, welcome, thank you for being with us in Euronews and congratulations for this award. Why do you do this job, specially, the war part? The British photographer, Don McCullin, says that you can only be a war photographer in the long term if you have a purpose? What is your purpose?*

Because people have to know what’s going on in the world. And when there’s a war there’s so much at stake for the people involved in the war and for the rest of the world. Photographs can get behind the political rhetoric that is always surrounding a war. It creates a kind of justification for the people who are conducting the war.

And photographers are on the ground; they are seeing what is happening to individual human beings. They are showing the effect of the war and holding accountable the decision makers and policy makers that are conducting the war. And this is a way in which public opinion can be brought to bear, to pressure for change.

*Do you think that a picture can be an antidote to war?*

Yes. I think that, in a way, a picture that shows the true face of war, is an anti-war photograph. In my experience in seeing what war does to people and societies it would be very difficult to promote that. So, I think that photographs that show the true face of war, in a way, are mediating against using war as a mean of conducting policy.

I think that there are things worth fighting for in this life and I think that people have to defend themselves, but I also think that we should be aware of where war leads, what are the inevitable consequences of war in human terms. And we must never forget it and we must deeply think upon it before people commit to fight a war.

*You have covered dozens of wars. Is there one that marked you more than the others?*

When someone is suffering, when someone is being victimised it is hard to say one is more important than the other. I think they all are equally important. But having said that, the genocide in Rwanda was something that was so extreme and unusual that it was something very hard to, actually, understand in my mind how it could be that 800,000 to a million people were slaughtered by their countrymen in three months, using farm instruments as weapons.

There’s a moment that comes when somebody is raising a machete or an axe about the head of an innocent person, what allows them to bring that weapon down on their neighbors? I can’t actually understand that.

Black and white

*Most of you work is done in black and white. If your purpose is to portray reality, reality is not shaped in black and white, but in color. Why black and white?*

That’s right, black and white is not real, it’s abstract. But what it does do is, I think, it distills the essence of what’s actually happening, because colour itself is just a strong phenomenon, in a physical sense, that in a way it competes with what is happening in the picture. It tries to become the subject of the picture. So, if you abstract it into black and white, it distills the essence of what’s happening without competing with color.

*What makes the difference between a good image and an iconic image? What are iconic images made of?*

It has to be something very strong, genuine and deeply human expressed through the picture. It has to be a situation which has to be historically significant and you know, in journalism you have to be on the right place in the right moment, which sounds simple but, actually, it’s extremely difficult, as you know.

I think it has to be the condition of public awareness of a certain event; it has to reach a certain point before a picture can become iconic. For example, the picture of the young boy Aylan Kurdi who drowned off the coast of Turkey, it came in a moment when the world was aware enough of that situation. Then it galvanised public opinion.

The picture of Kim Phuc, the young girl who was running from the Napalm in the Vietnam War. It happened in a time when there was enough awareness of the war and there were protests against the war. Then, that picture, again, galvanised public opinion.

*Speaking about that, hard impact images and mass media. You know, first hand, that publishers and editors are often reluctant to show this kind of images – you mentioned the Aylan Kurdi example, which is a very good one – and the most used argument is that by publishing these images we are some kind undermining the dignity of the victims. Does this make any sense to you?*

That people suffer does not mean they don’t have dignity. That people have fear does not mean they lack courage. That people are enduring difficult circumstances it does not mean they don’t have hope. Then pictures don’t undermine dignity, not necessarily. I don’t think that the picture of Aylan Kurdi undermined his dignity.

I think that it created a great deal of sympathy for the young boy, and for his family and for all of the immigrants. And if it had been a picture that was not dignified in some way, that did not recognise the sacrifice that had been made, then the picture would not have had effect.

*Well James Nachtwey thank you very much, it’s been a real pleasure to talk to you and take care.*

You are welcome.