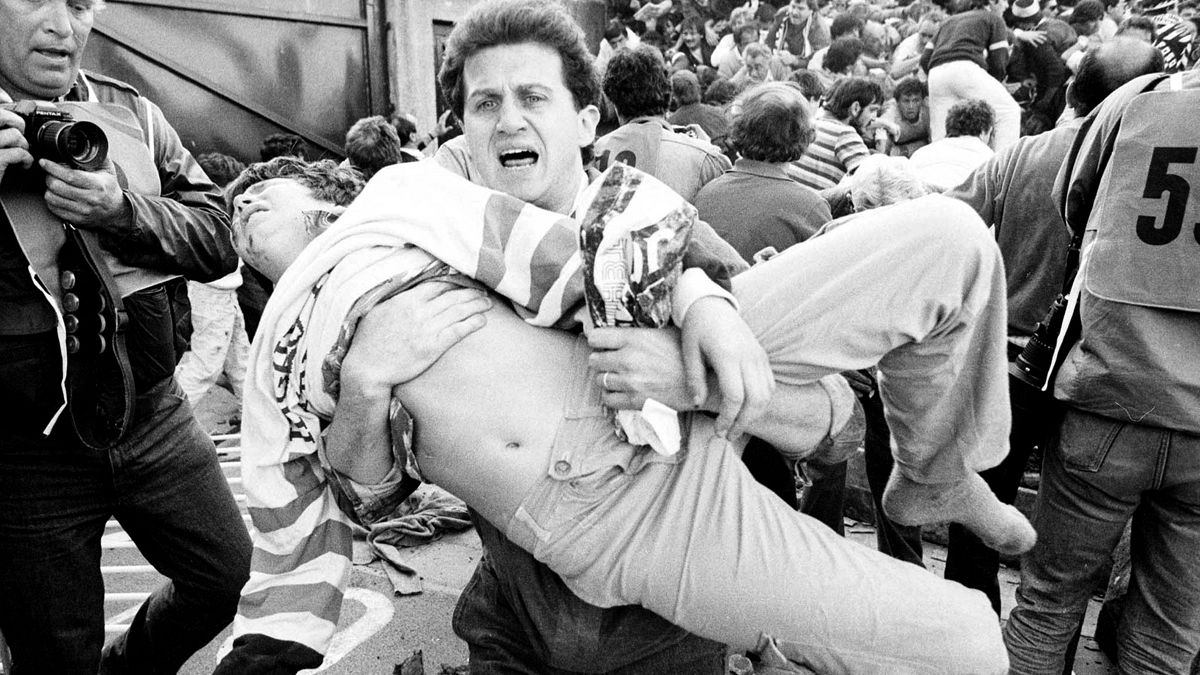

On May 29, 1985, 39 people – most of them supporters of Italian football champions Juventus FC – were killed inside the Heysel Stadium in Brussels

On May 29, 1985, 39 people – most of them supporters of Italian football champions Juventus FC – were killed inside the Heysel Stadium in Brussels ahead of the European Cup final against Liverpool FC. 600 others were injured. The tragedy unfolded live on television in front of an audience of millions. Here we look at the main causes and consequences of one of football’s darkest nights.

What were the causes?

Hooligans

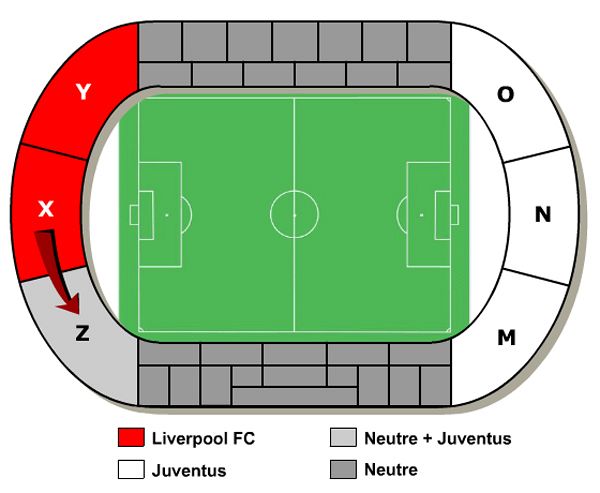

Ostensibly the disaster was caused by English football hooligans. Liverpool fans had been allocated tickets in Zones X and Y, while the Juventus fans were given tickets at the other end of the pitch, in Zones M, N and O. Zone Z, adjacent to the Liverpool fans, was supposed to be for neutral supporters. However many Juventus fans obtained black market tickets for this zone.

The year before Heysel, Liverpool had beaten AS Roma in the European Cup final in Rome. Many Liverpool fans were attacked in Rome after the match, and Heysel provided an opportunity for “revenge” not just for hooligans associated with Liverpool FC but also for other hooligan “firms” from across England who also made the journey to Brussels.

The year before Heysel, Liverpool had beaten AS Roma in the European Cup final in Rome. Many Liverpool fans were attacked in Rome after the match, and Heysel provided an opportunity for “revenge” not just for hooligans associated with Liverpool FC but also for other hooligan “firms” from across England who also made the journey to Brussels.

At around 19:00 local time, an hour before the scheduled kick-off, English supporters in Zone X and Juventus fans in Zone Z began to throw stones and other missiles at each other. The throwing intensified until, at around 19:45, a group of English fans breached a flimsy wire separation barrier and charged at the mixed supporters in Zone Z.

These fans in Zone Z, could not escape onto the pitch as authorities had erected a barrier, so they fled back towards the back of the stand and began climbing a wall to escape the oncoming hooligans. Most of the casualties occurred when this wall collapsedas supporters from Zone Z were crushed either by the wall or the stampeding fans trying to escape.

The following day UEFA official Gunter Schneider said: “Only the English fans were responsible. Of that there is no doubt.”

British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher echoed this sentiment, saying “There are no words, there are no possible justifications; the blame is entirely for England.”

However Belgian judge Marina Coppieters published a report after an 18-month investigation in which she concluded that while English fans were culpable, the blame should be shared with Belgian police and authorities.

Fourteen Englishmen were eventually convicted of involuntary manslaughter but there was more to it than simply drunk English hooligans.

A stadium unfit for the occasion

Heysel – Belgium’s national stadium – was built in the 1920s and not adequately maintained. By 1985 it was in a state of serious disrepair. The outer wall was built of breeze-blocks, and many ticketless fans were seen kicking holes in this wall before the match in order to enter the stadium. Loose rubble and concrete provided ready-made missiles for both sets of fans. It has been argued that the fact the wall behind Zone Z collapsed may have saved lives, as more people could climb over it, but that it collapsed at all is testament to the decrepit state of the stadium. The wire-mesh fence separating rival fans in Zones X and Z was also grossly inadequate. The stadium had been condemned years before for not meeting modern safety standards and the 1985 final was intended to be the last football match played there before renovation. Ahead of the match, Liverpool FC Chief Executive Peter Robinson had urged UEFA to change the venue, as Heysel was not fit to host a match of such volatile potential.

Chaotic ticketing

The head of the Belgian FA, Albert Roosens, was given a six-month suspended prison sentence in 1988 for allowing tickets in the Liverpool zones to be sold to Juventus supporters. Many more tickets had been sold, or counterfeited, than the stadium capacity allowed. Around 60,000 people gained entry to a ground meant for 50,000. Fans with tickets have since recounted that those tickets were never checked at the turnstiles.

Belgian authorities knew of this but, fearing violence, were keen to keep supporters inside the stadium rather than outside in the streets of Brussels.

Poor policing

The Belgian police were woefully under-equipped to deal with what happened. Only five officers were initially posted between the rival fans in Zones X and Z despite warnings before the match that violence was likely.

When the match organisers wanted to calm the crowd so that the match could get underway, it was the players and not the police who were asked to intervene; captains Phil Neal and Gaetano Scirea took to the stadium tannoy and even ventured onto the track around the pitch to appeal for calm.

The controversial decision to allow the match to be played, despite it all, was made in order to allow Belgian police reinforcements to organize their response to violence outside the stadium after the match. The officer in charge of security in Zone Z, Johann Mahieu was convicted of criminal negligence years after the tragedy.

The aftermath

English clubs banned from European football

Margaret Thatcher was among the first to call for English clubs to be banned from European competitions. UEFA did just that and English clubs would not play in the European or UEFA cups for another five years, six years in the case of Liverpool.

Impact on football stadia

Sadly the lessons of Heysel were not learned. Four years after Heysel, 96 Liverpool fans were crushed to death at a match at the Hillsborough Stadium in Sheffield. It was only after this tragedy that professional clubs in England were required to have all-seater stadia, to remove fencing in stands and install CCTV cameras.

Banning orders for hooligans

English football authorities introduced 3-month stadium bans for hooligans in 1986 but the country struggled with its hooligan problem for years after Heysel. It was only in the mid-to-late 1990s that serious progress was made in this respect: the launch of the Premier League in 1992 (and the cash injection that came with it) saw alcohol bans in stadia and a rise in ticket prices that “gentrified” football crowds in England and changed the demographic of match-going fans. Chased away from domestic football, English hooligans continued to misbehave abroad however, notably during a match against Ireland in 1995, the 1998 World Cup in France and during the 2000 European Championships in Belgium and the Netherlands. This led to the multiplication of banning orders, from fewer than 100 at the end of 1999 to more than 2,000 four years later.

It is generally accepted that football hooliganism is now much less of a problem for English authorities than it is in other European countries such as Italy and France.

The victims

Of the 39 people who never returned from the Heysel tragedy, 32 were Italian (two of whom were children), four were Belgian, two French and one was from Northern Ireland.

Rocco Acerra, aged 29; Bruno Balli, 50; Alfons Bos, 35; Giancarlo Bruschera, 21; Andrea Casula, 11; Giovanni Casula, 44; Nino Cerullo, 24; Willy Chielens, 41; Giuseppina Conti, 17; Dirk Daenecky, 38; Dionisio Fabbro, 51; Jacques François, 45; Eugenio Gagliano, 35; Francesco Galli, 24; Giancarlo Gonnelli, 20; Alberto Guarini, 21; Giovacchino Landini, 50; Roberto Lorentini, 31; Barbara Lusci, 58; Franco Martelli, 22; Loris Messore, 28; Gianni Mastroiaco, 20; Sergio Bastino Mazzino, 38; Luciano Rocco Papaluca, 38; Luigi Pidone, 31; Bento Pistolato, 50; Patrick Radcliffe, 38; Domenico Ragazzi, 44; Antonio Ragnanese, 49; Claude Robert, 27; Mario Ronchi, 43; Domenico Russo, 28; Tarcisio Salvi, 49; Gianfranco Sarto, 47; Giuseppe Spolaore, 55; Mario Spanu, 41; Tarcisio Venturin, 23; Jean Michel Walla, 32; Claudio Zavaroni, 28.