In the latest in a series of articles on how World War II changed forever the countries that fought it, Kirsten Ripper looks at Germany, the instigator of the conflict and a nation that would be torn in two in its aftermath.

German guilt for Europe’s suffering

In World War II, Germany brought immeasurable suffering and destruction to the whole of Europe. An estimated 60 million people were killed in the conflict, of whom around five million were German. Two thirds of the dead were civilians – among them six million Jews.

Adolf Hitler committed suicide on April 30, 1945. On May 8 in Reims and again on May 9 in Berlin, Germany’s military signed the unconditional surrender.

At the end of the Nazi regime Germany was almost totally destroyed. Some 12 million Germans were refugees – mostly from regions in the East that were now in Soviet hands – and looking for a new home.

The responsibility for WWII and the national sentiment of guilt shaped the role of German politicians and citizens in Europe for decades.

Photos: The German population had suffered terribly from carpet bombing, notably in towns like Dresden (left), but also carried a huge sense of guilt for the suffering of others; (Right) Some of the 8.7 million Soviet soldiers killed during the war

Never again: Holocaust and anti-semitism

Holocaust (the Greek word for “burnt”) or Shoah (the Hebrew word for “catastrophe”) refers to the mass murder of six millions Jews, or people that the Nazi regime considered Jews.

It was the declared aim of the Nazis to ban all Jews from Europe, Hitler’s “final solution to the Jewish question” that led to industrial mass murder.

Jews, but also Sinti, Roma, homosexuals and political opponents were persecuted by the Nazi regime. The worst horrors were the organised mass shootings and death by gas of death-camp prisoners from all over Europe.

It was only when the Soviet Red Army and then the Allied Forces liberated the concentration camps at the end of the war that the degree of the crimes became apparent.

The Allies tried to bring to justice the perpetrators of the Holocaust in the Nuremberg Trials.

Since the end of World War II, Germany has been trying to come to terms with anti-semitism and has made the denial of the Holocaust punishable by law.

The Shoah also explains a very special relationship between Germany and Israel, where Yad Vashem in Jerusalem remembers the six million murdered Jews.

Photos: Auschwitz (left) and the Yad Vashem memorial

Cold war and a divided Germany

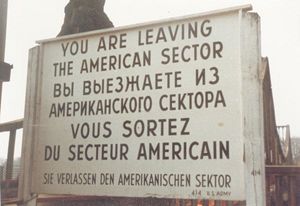

At the Yalta and Potsdam conferences in 1945, the leaders of the USA, the USSR and Great Britain planned the de-nazification, democratisation and demilitarisation of a post-war Germany.

These three ultimately victorious powers, along with France, shared the administration of Germany, which was carved up into four zones of occupation. Berlin – which found itself within the Soviet zone of occupation, or “Eastern Zone”, was also itself divided into four zones of occupation (sectors).

Immediately after the war, Winston Churchill spoke of an “Iron Curtain” that had descended across Europe, behind which the Soviet Union was hiding: “An Iron Curtain is drawn down upon their front. We do not know what is going on behind.”

The Iron Curtain separated the capitalist West from the Soviet, communist East and became the front line in a new conflict – the Cold War.

On May 23, 1949, the Federal Republic of Germany (known as West Germany) was founded on the model of Western democracies. Five months later the Soviet occupied Eastern Zone, along with East Berlin, officially became the “German Democratic Republic” (known as East Germany), a Soviet-style socialist state.

There followed a progressive separation of the two German states, the most visible being the Berlin Wall built by the Soviet-backed GDR in August 1961. The fall of the Wall in 1989 was the first big step toward German reunification, 44 years after the end of the Second World War.

Photos: Attlee, Truman and Stalin at the Potsdam conference (left); the western allies would occupy West Germany and West Berlin while the USSR occupied East Germany and East Berlin

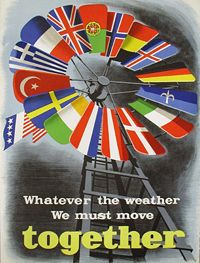

The Marshall Plan and German economic ‘miracle’

In Germany and in Europe most industries were destroyed after WWII, causing chronic unemployment and poverty. In 1947, the US Secretary of State George C. Marshall had the idea of a ‘European Recovery Programme’. It was designed to “contain” totalitarism and communism and to create markets for US products. Great Britain, France, Italy, Germany, Austria, Greece and the Benelux countries received help from the USA. Washington invested 13.2 billion dollars into the European economy. For many experts this provided the basis of what is today the European Union.

In the 1950s the German economy was beginning to experience what Germans described as a Wirtschaftswunder (Economic Miracle). The Christian Democrats had introduced the so-called “social market economy” and industry grew by 185 percent between 1950 and 1963. To rebuild Germany, the economy needed extra hands and from the mid 1950s a steady flow of “Gastarbeiter” (guest workers) were recruited – first from Italy, but then also from other countries including many from Turkey. West Germany had been transformed within 15 years from a Nazi disaster zone into a prosperous, immigration state.

Photos: a poster (left) promoting the Marshall Plan; (right) Volkswagen Beetles poured off production lines and became a symbol of the ‘Economic Miracle’.

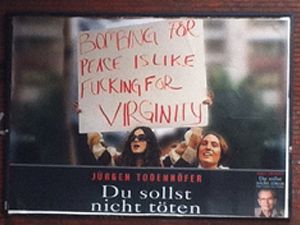

Pacifism and the new role

After the bitter experience of the Nazi regime and Second World War, Germans, both in East and West turned away from militarism. Although West Germany decided in the early 1950s – despite strong protests in Parliament and among the public – to follow East Germany in rebuilding an army and (unlike East Germany) join NATO, West German soldiers took no part in international combat missions until German reunification in 1990.

Although the end of the division forced Germany to abandon its passivity and redefine its role in the Western defense alliance, a pacifist attitude and a certain skepticism about military activities in Germany – regardless of generational change – can still be observed today.

Photos: an image of a peace demo is used to promote a book in Essen; (right) ‘Non-violence’, bronze sculpture by Carl Fredrik Reuterswärd exhibited in Marl park, Germany.