On April 12, the far-right Jobbik candidate Lajos Rig won a by-election in the individual constituency of Tapolca. The election followed the death of incumbent former Fidesz MP Jenő Lasztovicza in early January 2015. An electorate dissatisfied with the performance of the government, appears to have turned to the political party it considers capable of defeating the ruling Fidesz. Fidesz’s “central power field” strategy that worked well in 2014 has suffered a setback, as has the myth that Fidesz can stop the rise of the far-right. Jobbik can consolidate its position as the main challenger to Fidesz, and could even go first in the polls, writesthe Political Capital Policy Research centre.

Turnout matters

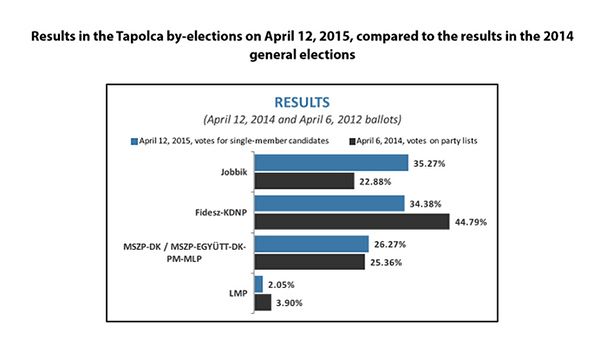

As the turnout rates below suggest, in the two by-elections held this year almost a quarter of Fidesz supporters have abandoned the party. Jobbik on the other hand has seen its support jump by half. However, due to lower turnouts, in earlier votes in both Veszprém and now in Tapolca (both are constituencies in Western Hungary) Fidesz’s rivals managed to attract more voters to the polls than those voting for the respective party lists one year earlier in the same individual constituencies. Jobbik could gain plenty of new voters, especially from small villages.

Jobbik has been able to expand its support for three main reasons: their moderate shift; their comfortable position as the only relevant, “clean” political force that has not discredited itself in power; and the lack of strong and united left-wing opposition.

Research does not indicate any significant rise in anti-Semitism and racism in Hungary as the driving force of Jobbik’s current rise and success. The success of Jobbik suggests that most voters no longer look at the party as extremist: taboos that once kept a large number of undecided voters away from Jobbik seem to be evaporating.

This might sound surprising if one considers the views of Jobbik candidate Lajos Rig. He has been accused of sporting a tattoo similar to the logo of the German SS and has repeatedly published posts on Facebook with a clear anti-Semitic and racist tone. In one of his posts he shared his thoughts about the Roma being biological weapons controlled by Jews in order to eliminate the non-Roma and non-Jewish population of Hungary.

Jobbik’s electoral victory has confirmed what many have maintained for quite some time: there is no limit to Jobbik’s expansion, and the process could only be checked by its political rivals, although there are no signs of this happening any time soon.

Following parliamentary and municipal elections, the results of the latest by-election serve as additional proof that Jobbik’s attempt to re-brand itself as a moderate party has been largely successful. All this consolidates party president Gábor Vona’s position within the party: in the future he can move the party in the direction of the centre-right with more confidence. Simultaneously, the result offers Vona the opportunity to eliminate his opponents inside the party who accused him of being “soft”.

Similar to what we have seen in Veszprém, Jobbik’s victory can also be attributed to the fact that it fielded a local candidate, working hard up and down the electoral district and managing to profit from an anti-establishment sentiment. The current victory will clearly have an impact on support for Jobbik; there may be a widespread perception that Jobbik is a party capable of replacing Fidesz, and with this the party may consolidate its second place or even take the leading position in public-opinion polls.

Ruling party Fidesz: house of cards?

The governing party’s “central power field” strategy (built on the concept that Fidesz remains the sole governing force whose position cannot be challenged by weak opposition forces at either end of the political spectrum) has failed. Moreover, it is precisely in this fundamentally right-wing district (in April 2014 the Fidesz candidate received almost as many votes as his challengers from the right and the left combined) where the “central power field” strategy would have been expected to work. Presumably, the party is in an even poorer condition nationwide.

The current election also made it clear that the party has no magic bullet when it comes to engaging voters: neither the so-called ‘Kubatov-lists’ (databases used for door-to door campaigning), nor Victor Orbán’s personal appeal have been enough to guarantee victory at the polls.

The interim election in the constituency around Tapolca has also confirmed the assumption that the durability of established institutions is a function of the prevailing balance of power in party politics – and not the other way around. As hard as Fidesz has tried to consolidate its power through a series of election reforms and centralisation keeping everyone in a dependent position, once support is withdrawn the whole structure collapses like a house of cards.

With all that, Fidesz may attempt to redraw the electoral system once again (after Tapolca, the governing party may reconsider whether the elimination of the second-round ballot would serve its purpose in the 2018 general election). However, to pass another reform Fidesz would have to find an ally in Parliament as it lost its two-thirds majority in the Veszprém by-election (currently it has 131 MPs in a 199-seat parliament and 133 would be needed for the two-thirds).

At this point there are no signs that Fidesz is capable of adjustment, and even the recent loss, albeit close, is unlikely to force it to change course. Apparently, Prime Minister Orbán hopes to turn the tide of public mood, putting his trust in the government’s next secret weapon: tax-cuts. In the meantime, with intensifying internal conflicts, recurring management blunders, a rhetoric that ‘the electorate will understand it all by the end of the term’ and the collapse of the party’s media and intellectual background, increasingly the third Orbán administration’s future resembles the ordeal faced by the leftist government after 2006.

In addition, apparently Fidesz has no adequate response for the Jobbik phenomenon; for years, having essentially failed to attack its rival to the right on ideological grounds, in the final stretch of the campaign it opted for a tactic of the left that has clearly failed in the recent past: the stigmatisation of Jobbik (“Jobbik is a neo-Nazi party” – has been the mantra of leading Fidesz politicians in recent days). Although Fidesz will continue to maintain that it represents a guarantee against the far-right, the message no longer carries much weight either in Hungary or abroad.