Students, the unemployed, lawyers, internet dissidents…they were all actors in the Tunisian Revolution. More than four years after the fall of Ben Ali, they express pride and disillusion. Interviewing them allowed euronews to take the pulse of Tunisian society, four years after everything changed.

On December 17th 2010 Mohamed Bouazizi, a young barrow vendor of fruits and vegetables had his equipment confiscated by police. He burned himself alive in protest in front of the governor’s office in Sidi Bouzid. He died of his wounds two weeks later.

In the meantime the streets take up his cry of injustice, erupting in demonstrations followed by riots and clashes with the police. A slogan is born, “Work, Freedom, Dignity” that mobilises thousands in a matter of days. Protests then spread to poor rural areas before, just 28 days later, the people’s demands for Ben Ali to resign are irresistible. Crowds fill Bourguiba avenue in the capital, Tunis, and on the 14th January Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali and part of his clan brusquely leave office. A 23-year-old authoritarian regime crumbles, and dies.

Four years later Tunisia has a new government after a free election. Tunisia’s transition to democracy is hailed as a success. Tunisia is cited as a special case, an exception in the disappointing post-Arab spring .

However many Tunisians say the revolution is not complete. Its ambitions for social justice are far from being achieved and many of its supporters are torn between euphoria, pride, and disappointment.

These interviews were conducted before the Bardo Museum killings.

Timeline

- 20 March 1956 : Tunisia wins independence from France.

- 8 November 1959 : Habib Bourguiba becomes President of the Tunisian Republic.

- October 1987 : Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali becomes Prime Minister.

- April 1989 : Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali becomes President.

- 17 December 2011 : Mohamaed Bouazizi sets himself on fire in Sidi Bouzid.

- 14 January 2011 : Zine El Abidine Ben Ali flees to Saudi Arabia.

- 23 October 2011 : Tunisia's first free election: the Ennahda Islamist party wins a majority in the National Assembly.

- 6 February 2013 : Opposition leftist Chokri Belaïd is murdered.

- 25 July 2013 : Left Nationalist member of parliament Mohamed Brahmi is murdered.

- 29 July 2013 : the Mount Chaambi attack, in which eight soldiers are killed.

- 18 December 2013 : A technocrat government takes over from the Ennahada-Left coalition

- 26 January 2014 : A new constitution is adopted , the country's third.

- 26 October 2014 : Legislative elections are won by the anti-islamist Nidaa Tounès party.

- 21 December 2014 : Beji Caïd Essebsi is elected President.

- 18 March 2015 : Islamic State claims responsibility for the Bardo Museum attack.

We had wanted this revolution for years

Mohamed Ameur chain-smokes his Boussetta filters, “At least fags cost next to nothing”, he says in a sarcastic tone. This primary school teacher is close to retirement age. In the alleys of the Ettadhamen he picks his way carefully around potholes, waving at familiar faces. He then slows for Ibn Khaldoun avenue, the main shopping street that plunges down into Intilaka, one of Tunis’s dense, working-class districts.

His face lights up; “This street was thronged with people, there were at least 100,000 here. This is where it all began,” he claims, referring to the Ettadhamen rising on January 12 2011. It was the starter’s gun for a new wave of protests that would give Ben Ali pause for thought.

The name of the district translates as “Solidarity” in Arabic. It is Tunis’s most populous suburb; the locals say it is Africa’s most populous. It is a city within the city, built up during the rural exodus from the countryside, with a population of 250,000. Soldiers stand at certain crossroads, showing Ettadhamen’s “frontier” with the rest of Tunis.

“The authorities consider this as a ‘rural’ zone”, sighs Mohamed Ameur, walking past bored-looking officials normally part of the rural scenery. This is only a few underground stops from the centre of the capital, but it shows the unseen side of the much-vaunted “economic miracle” of the Ben Ali years.

Ettadhamen’s young people honour their friends who died during the revolution, (Photo : @Agnès Faivre)

“Things got worse for many families during the 1990s” says Khaled Salah. This Primary School Headmaster has seen parents struggle to buy their children books, or even packed lunches. Other have taken their children out of school to sell stuff in the streets. “They see their fathers and brothers out of work and they say ‘Why study? There’s no future for us here’”, he says. “We tell them there may not be a professional future but there is an intellectual one and that is more valuable”.

Mohamed Ameur thinks the liberal reforms enacted at the end of the 1980s hurt the most vulnerable in society. “School remained free, but all the rest was difficult,” he says. Aside from increasing poverty a growing climate of oppression set in, a suffocating lack of freedom, so teachers gradually changed the message they were giving their charges.

“When we taught them that the President of the Republic had a maximum number of terms in office and that they didn’t understand why he stayed on, we told them ‘So go and protest’”, says Mohamed with a smile.

In Ettadhamen teachers are seen as the ‘guardians’ of the revolution. Most of them are members of Tunisia’s General Workers’ Union, historically very important in Tunisia. When police officers deserted the district in the early stages of the revolution it was teachers who tried to channel the revolutionary spirit, making posters, slogans, and organising stewards to monitor the demonstrations. Guard duties were organised to protect citizens as the clashes with police in Ettadhamen were particularly violent, leading to the deaths of at least nine young people.

The protests continued nonetheless culminating on January 14 in a march on the Interior Ministry on Bourguiba avenue in Tunis. “I saw one of my students in the crowd, and he threw himself into my arms, crying ‘At last!’. It was at this moment, adds Mohamed Ameur, that people started to dream…

14 January demonstration on Avenue Bourguiba in Tunis

Also in the massive crowd that day was Imen Bejaoui.

“We had wanted a revolution for years” says someone who became a practising lawyer in 2006 and saw at first hand “Ben Ali’s hand hovering over the courts”. Despite the legal system being rigged, Imen Bejaoui spoke out, condemning the “Ben Ali system” based on cronyism, embezzlement of public money, and bribery. Weeding out the rotten elements has barely begun.

“We fought Ben Ali everywhere, in the courts, in the ministries, because he was everywhere. He had his ‘yes men’ placed, his own network, and we were among the first to take to the streets,” says this young woman who is now President of Tunisia’s Young Barrister’s Association.

On January 14 barristers lined up to keep the police away from the people around the Interior Ministry. It was a dramatic symbol, cordoning a building in which so many had been tortured or died during the Ben Ali years.

“Behind us we had three groups of police in full riot gear, and in front of us we had the citizens. I will never forget the look on their faces. They were screaming for Ben Ali to go, for the Trabelsi, (Ben Ali’s second wife’s family), clan to go, but when they looked at us, there was a lot of respect.,” remembers Imen Bejaoui. That night, when she heard that the presidential plane had left the country, she was filled with joy; “It was extraordinary, I said to myself, that’s it! We will have all the freedoms we want now.”

(function(d, s, id) { var js, fjs = d.getElementsByTagName(s)[0]; if (d.getElementById(id)) return; js = d.createElement(s); js.id = id; js.src = "//connect.facebook.net/en_US/sdk.js#xfbml=1&version=v2.3"; fjs.parentNode.insertBefore(js, fjs);}(document, 'script', 'facebook-jssdk'));> Les avocats contre Ben Ali et sa mafiaPosted by Sarra Hamdy on Tuesday, December 28, 2010

Imen Bejaoui during the 28 December 2010 Barristers’ demonstrations in front of Tunis’s central courtJournalist Lilia Weslaty was also very active in the first hours of the revolution. The memories of the evening of January 13 are what she remembers most vividly. In Ben Ali’s last-ever speech as leader he announced “total freedom of information and the internet.” Weslaty calls this a “magnificent “ moment. She trained as a teacher before, by accident, discovering the chains of censorship in 2002.

She was looking for information on Tunisa’s constitutional referendum but could not get a single page to load. A friend then showed her how, by using proxy servers, she could break through the firewalls and access banned sites. The full extent of Tunisian censorship then became apparent. Lilia could hardly believe her eyes.

“I had no idea how completely disconnected we were from reality,” she admits. In the wake of the blogger and cyberdissident movement of the early 2000s Lilia learned how to break into blocked websites, and using seven pseudonyms and several Facebook identities she started to distribute videos of torture victims. Then she moved on to exposing censorship, gathering data, and revealing secrets. She discovers a host of new friends on the web.

Ammar 404 was Tunisian’s nickname for censorship, because the internet would display “404 error” whenever access was refused to a blocked web page.

On January 13 2011 Lilia Weslaty, like millions of Tunisians, (in 2011 there were an estimated 4 million internet users in Tunisia), was able to click on YouTube, Dailymotion, Nawaat, an independent news site created in 2004, or Tunisnews, run by Islamist opposition figures in exile. All previously banned sites were now open, and in one night the state’s cybersecurity apparatus was swept away and Tunisia ceased to be, in the words of activists Reporters Without Borders, “ an internet-hostile country”.

“We witnessed an explosion of news everywhere. the good and the bad, even the untrue. It was a cacophony, but at last we could breathe freely,” says Weslaty with a twinkle in her eye.

Lilia Weslaty, journaliste, revient sur la fin du blocage d’internet et sur son parcours de cyberdissidente

Journalist Lilia Weslaty discusses her cyberdissident past and how the censor was defeated in Tunisia. (French)

The revolution’s gains

Lilia Weslaty of Webdo (Photo : @Agnès Faivre)

Since July 2014, Lilia Weslaty has edited the online newspaper Webdo. The office has space for three journalists and a Community Manager to sit around a table, headphones at the ready to glean data from Facebook, Twitter or YouTube. Previously at Nawaat, the media of reference run by a bloggers’ collective, Lilia Weslaty sets the tone.

“We want to create here an objective media outlet, we want to do good work without supporting any party, or getting revenge on the figures from the old regime. We want to do journalism, real journalism,” she insists. That is no easy task as the media landscape was for a long time the monopoly of the ruling party and its friends. Today it is being shaken up from top to bottom.

It is a nebulous environment, with former regime apologists rubbing shoulders with young guns who want to change everything, to those who have changed sides and ostensibly support the new deal.

In Nawel Bizid’s opinion, “Webdo” incarnates hope, and a new seriousness;

“Alternative media, especially those who stream blogs live, have taken over from where journalists left off. They give out real information,” says this young woman who trained as an A&E anesthetist before giving up medicine to become a journalist in 2011. However, she only followed the revolution form a safe distance 2011, more out of curiosity at the start, and driven by pity for the plight of Mohamed Bouazizi.

“He didn’t set fire to himself for the cause of media freedom, but for dignity, and the right to work,” she stresses. It was only after January 15 in her opinion that things really kicked off, when people realised everything had to change. Webdo often sent her into the field to file reports, and she made community and society pieces her speciality. Bizid is sceptical about the political responses to the crisis so far, but remains happy that freedom of expression, the key to the future in her opinion, is surviving. “As long as we can express our unhappiness we have a chance to evolve.” she says.

Pour Nawel Bizid, journaliste, le changement commence après la chute de Ben Ali

In Nawel Bizid’s opinion real change came after the fall of Ben Ali (French)

The Webdo office (Photo : @Agnès Faivre)

“We are learning”, says Maher Chaabane, Webdo’s Deputy Editor.

“You need at least 20 years to change mentalities and adapt.”

Chaabane is a former journalist at Tunis Hebdo, a general interest paper with a pronounced taste for the satiric but which had to buckle under the censor’s rule. He is re-learning his journalism, picking up the tools of the web trade, and reporting in an atmosphere overturned by free speech and free, multiparty elections. It has changed the nature of political reporting.

New rules, new media

He covered the first elections, his first. No more late-night smoke-filled editorial meetings with calls to come to the interior ministry for the reading out of Stalinist approval ratings for the ruling RCD party. ,

Webdo went out to the regions to report, it followed the sometimes vicious debates between political parties, and observed in the polling booths during the election. “We followed the results live as they came in, biting our fingernails,” he says. Was he able to detect a new mentality? “No-one was interested in politics before the revolution. Either through fear, habit or apathy, people didn’t express themselves”, says Maher Chaabane.

Maher Chaabane, journaliste, redécouvre son métier après la révolution

Journalist Maher Chaabane rediscovers the joys of his profession after the revolution. (French)

“How can one fail to be proud of what was accomplished during the revolution?” asks Lilia Weslaty. Tunisia’s journey towards a state with the rule of law is very positive, she says.

A new press code came into force on November 4 2011, giving journalists more rights. The independent Communication and Audiovisual High Authority or HAICA was set up in May 2013 to protect and regulate the media.

The transitional authorities also gave Tunisia a new constitution, replacing the 1959 version. Adopted on January 26 2014 it enshrines freedom of expression and belief, equal rights for women, the principle of parity in elected assemblies, and the banning of physical and mental torture. It is the most progressive document of its kind in the Arab world.

“It is an excellent constitution, which also includes the right to strike,” says the General Secretary of the UGTT, Hfaiedh Hfaiedh, proudly. “We are very happy with what our nation has done. Tunisia is not Egypt, it is not Libya. We are showing the world that it’s possible for an Arab state to make the transition to democracy, despite all the difficulties, the terrorism, the assasinations, or the conflict on the Libyan frontier,” he says.

UGTT headquarters in Tunis. The powerful union can count on 750, 000 members (Photo : @Agnès Faivre)

Murders most foul

And yet it would not have taken much for the country to tip into political violence. The killing on February 6 2013 of lawyer Chokri Belaïd, the leader of a left-wing party, sparked a wave of protests. The attack crystallised the political tensions between Ennhada’s Islamists, with a majority in parliament, their left-wing coalition partners in the Constituant National Assembly, and the opposition’s forces.

The murder of leftist nationalist MP Mohamed Brahimi on July 25 followed four days later by eight soldiers killed on the Algerian border by the al-Qaeda-affiliated Okba Ibn Nafa brigade polarised opinion even more. Tunisians were faced with a choice between two camps sworn to fight to the death; the Islamic Conservatives or the Secular Progressives.

Larbi Chouikha, politologue tunisien, revient sur la bipolarisation du paysage politique en Tunisie.

Larbi Chouikha is a political analyst. He reflects on how Tunisia’s political landscape became polarised between two camps. (French) There is power in a union

The situation only calmed down in the autumn of 2013. The UGTT managed to get everyone on board for a “National Dialogue”. Negotiations began with the formation of a new technocrat government that would lay the foundations for the 2014 elections. The union mobilised its network of 750;000 members to re-enter the political arena it had deserted, and again provide and support MPs in parliament or government. It was a return to real politics for the UGTT.

“Sometimes the workers would say to us ‘Bravo, you led us through the elections but what have you done for us?’ We replied that our electoral success was also a guarantee for them, it was a promise,” says Hfaiedh Hfaiedh. “The union’s main message was ‘be patient, the hardest has been done already’, but Tunisian society did not seem to echo that feeling of success, that feeling of having done away with authoritarianism in favour of democracy. Most people were only concerned with relaunching the economy.”

However everyone, whether they are frontline activists, protesters, anti-censorship and corruption campaigners, or just ordinary students, workers, or the unemployed agree on one thing. The time when the walls had ears is over. It is now possible to freely express an opinion in Tunisia or debate an issue in a bar, cafe, or front-page article.

“The system of repression set up by Ben Ali to lock down society broke on January 14,” says political analyst and human rights activist Larbi Chouikha. “Among the gains of this revolution are the freedom of expression and the liveliness of civil society. We have seen the birth of thousands of associations or clubs. It’s hard to know how many there are exactly, or how many will survive. How many of them actually have any economic activity? Five thousand? Fifteen?

One thing is for sure, they are not the fake government-controlled pseudo-NGOs of the pre-revolutionary period.

The terror threat, inequalities, or poverty – three things the revolution has not solved

Offices of the Tahadi Association based in the Ettadhamen district (Photo : @Agnès Faivre)

Youth makes a stand

Back in Ettadhamen we have a meeting near to the last stop on line five of Tunis’s underground, one of the gateways to the city. Tahadi is an association that was created the day after the revolution. The office is busy even on a Sunday. Shaïma is a 20-year-old management student who also gives hip-hop lessons. There is also Souhaïl, a 32-year old school assistant, a 37-year old singer and philosophy fan, Wissem, 25, who is a design student, and Lazar, a 27-year-old computer scientist.

They all have one thing in common; they love their home district and its street art, and they love human rights. A group of women meet nearby presided over by Fatiha;

“We explain the constitution to them, and what their rights are. We need to help protect these women against fundamentalism because this is one of the cradles of Slaafism,” says Wissem.

Tahadi is the Arabic word for challenge. The association wants to tackle above all the sidelining of Ettadhamen.

“This collective spirit is new here. For me it means thinking about peace. I have a lot of ideas,” assures Mounir.

Souhaïl says it is all about generosity; “Joining an association had been my dream”, he says, insisting on the wold dream. In Ettadhamen all he saw was growing youth unemployment “quickening after the revolution. I wanted to help the people in my district, where the problems were poverty and insecurity.”

The school assistant looked on as radical Islamists, some of them former classmates, “who left school too early” he says, gained ground. “Before the revolution they hid, they were scared of the dictatorship, but between 2011 and 2013 they were everywhere, above all in the mosques where they imposed their will. “Describing the confrontation with the fundamentalists and their rigidly expressed message became a big problem,” frowns Souhaïl.

“It was a war,” says Lazar. “There were very aggressive attacks. They have already burned our offices down once, and they love to spread fear. I feel threatened, but from what enemy? I can’t identify them.”

Lazar loves his rap and graffiti, covering the walls of Tunis with his pro-democracy slogans, but he feels the people living here have paid rather a high price for this freedom of expression.

Lazar, a voluntary worker in Tahadi,loves street art.Here he poses in front of one of his portraits of themurdered opposition MP Chokri Belaïd,assassinated on February 6 2013.(Photo : @Agnès Faivre)

The Fundamentalist flood

Mohamed Ameur, the primary school teacher from Ettadhamen, declines to talk about the rise of religious fundamentalists in jhis district. It already has a bad enough image as a “nest of Salafists” since the revolution, a new stigma he would rather do without.

“Everyone is scared to come to this part of Tunis. We can see the deterioration in the water supply system, the electricity, or the roads. Prices in the market are no longer controlled. No representative of the public services comes here any more,” he says sadly. The feeling of abandonment is only getting stronger in Ettadhamen, where the state only seems ready to intervene with mass police raids in certain mosques and Islamic schools.

This followed Tunisia’s classification of the radical Islamic group Ansar el-Charia as a terrorist organisation in August 2013. Dismantling the group proved to be difficult.

“Quite a few of our children were leaving to go on jihad in Syria or Libya,” regrets Mohamed Ameur. The teacher is worried about schools’ role in the future; less about education and more about babysitting and keeping the young out of trouble, which it has been doing more and more of over the last four years.

“Our classrooms are in a terrible state and we are short of teachers, but the education ministry says there is no money, and sends us supply teachers”, explains Mohamed Ameur. He too is feeling let down by the government.

The reasons for revolution remain

“It’s high time social issues were taken seriously,” says the president of Tunisia’s FTDES, or Economic and Social Rights Forum Abderrahmane Hedhili. “The interior minister says it has stopped more than 9000 young people from going to Syria , but there are at least 2500 Tunisians fighting there, so apart from the security measures already taken what is the government doing to dissuade these young people attracted by these Salafist colonists?”

A longtime activist, Hedhili wants to warn Tunisian society that there is a disconnect between the aspirations of the people as expressed in several social movements since the end of the first decade of the 21st century, and the proposed political solutions. It is as if the two spheres, society and its political class, haven’t been able to forge links.

So the revolution just comes in the wake of other outbursts of protest,the latest in a series of revolts against official indifference. The most notable was the miners’ revolt in the Gafsa basin in 2008 which was put down harshly by police. In this southern region, rich in phosphate, but also rural and poor, thousands of workers spent six months campaigning against poverty, inequality, and corruption.

These were exactly the same demands that brought thousands onto the streets in december 2010 in Tunisia’s poorest regions, but they are demands that apparently go unheard. Successive port-revolutionary governments have continued to ignore these demands says Abderrahmane Hedhili;

“We were confronted with a sort of social uprising and we didn’t take into account the deep changes that Tunisian society had gone through,” he laments.

The FTDES notes that more and more young people are tempted by jihad, black market commerce, or illegal migration, which has risen by 50% since 2011. All told it accounts for 30,000 departures per year.

Another sign of the social distress that has hit young people since the revolution is the school dropout rate. Around 100,000 students are quitting school every year. A new phenomenon in Tunisia which society is only just coming to grips with is suicide, which is mostly taking those under 35.

Academic achievement counts for little in jobs market

However Jowhar, Dalila, Mounira and Fatiha, four youngsters aged between 33 and 40, “qualified unemployed” people, are not running scared. This social-professional category, the “qualified unemployed” was one of the driving forces behind the revolution. It has even been recognised politically, with national representation since 2006 in the UDC, or Union of Qualified Unemployed, and has around 16,000 members. While unemployment is at around 15% nationally, for this category the figure is 30% says the National Statistics Institute.

The UGTT says it is more like 45%.

The young qualified unemployed demonstrate in 2012

“To find a job you need to know someone, or have a bribe ready. Without that you’ll get nothing,” complains Dalila. She has a Masters in Communication, but can only get work as a shop assistant. Today she has met fellow jobseekers during a half-day course in Tunis, and with them she goes off for a break in one of Tunis’s splendid oriental-style cafes. In a little while they will return home to Mahida, a coastal suburb that has become ‘Emigration Central’ for the young. Dalila says many young people have ended their lives here.

“There’s no work and no-one has any money” says Jowar, who is a qualified accountant and has worked as a school monitor for the last five years. “Every day you have to choose, either it’s macaroni, or it’s tomatoes,” he says. That comment gets everybody smiling, but as soon as the subject turns to the jobs market faces harden around the room. Everyone has something to say, an experience to recount. They speak of endless courses, cash-in-hand jobs, the black market, and the host of “little jobs” on two or three-month contracts.

Everyone has a pile of diplomas from the various courses they have been advised to take, a pile almost as high as the rejected job applications. They all talk about their interviews, the setbacks, insults, and refusals they have had to soak up. They are visibly relieved to talk about it, to get it out of their system. Jowar cannot shut up; it is unclear if he is expressing deep despair or anger. He says he is “sickened”.

“It’s not our turn,” sighs Fatiha, taking a more fatalistic approach.

They are, of course, all single. “To get married you need a stable job, and have the money to pay the rent,” says Dalila. So they live with their parents. This is a common situation. “The worst thing is when the children sleep in the same room as the parents,” continues Dalila.

For these young people the only thing that the revolution has brought them is freedom. They feel totally estranged from what they describe as “this business class” that seeks to influence the political players and is only willing to “dole out a few painkillers to keep Tunisia from agony”.

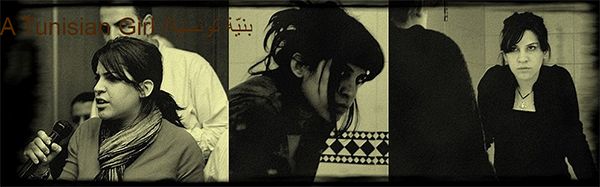

Lina Ben Mhenni comments on political and social events in her blog ‘A Tunisian Girl’ (Photo : @Agnès Faivre)

“Today we still have to face exactly the same problems as we did under Ben Ali. Tunisians came onto the streets to demand freedom, dignity, and jobs, but they have gained nothing,” says Lina Ben Mhenni.

She insists that social frustrations have not been taken into account in any of the post-revolutionary policies to emerge from government. This well-known blogger hit the headlines in 2008 for her coverage of the miner’s revolt, and she continues to be a thorn in the authorities’ side, camera in hand, covering Tunisia’s latest political, social and judicial news in her ‘A Tunisian Girl’ blog.

But there has been a change since 2013, when she was given police protection. “The Interior Minstry discovered that my name was on a list seized from an Ansar el-Charia terrorist cell,” she says. She is contemptuous of those foreign reporters who flooded into Tunisia during the revolution and went to the furthest-flung, poorest parts of the country.

“I wanted to show the whole world the reality of our situation,” she says. Mhenni wanted to preserve and honour the memory of those who died or were injured during the revolution, some 300 people according to the UN. She also wanted to see reforms put in place in the media, the police, and the justice system. Mhenni is very critical of delays in reforming these three institutions. The transition from dictatorship to democracy appears endless.

Les revendications des révolutionnaires n'ont pas été entendues selon la blogueuse Lina Ben Mhenni« je voulais montrer la réalité des choses »

The revolutionaries’ demands have not been heard according to blogger Lina Ben Mhenni. “I wanted to show the reality of things” (French)

A Tunisian Girl,Lina Ben Mhenni's blog

The committee “L’Instance Vérité Dignité”, has been given the responsibility of investigating human right violations committed between 1955 and 2013. It was created in June 2014. but it had to wait nine months before being given a budget to allow it to go to work. This is much too late in Lina Ben Mehnni’s opinion;

“Today I see people who were implicated in crimes committed during the Ben Ali regime in positions of power,” she says ruefully.

While many influential figures in civil society have been calling for the process of transitional justice to be speeded up, political analyst Larbi Chouikha instead paints a picture of institutions advancing on crutches, hobbled since the revolution. “We can see two contradictory universes existing side by side, those who have a real desire for reforms, and others who are full of doubts and only seek to protect their privileges,” he says.

This transitional justice is a new and vital stage of development for Tunisia. The country has not only social challenges but economic and security issues to face. The revolution may have lifted the veil on what was hidden in the past. Poverty was once censored from the press, and religious fundamentalists were repressed.

The security vacuum that followed the fall of the Ben Ali regime and the grinding social distress have created fertile terrain on which radical Islamic groups can flourish. The revolution’s leading figures are keen to stress that the security situation must not take the priority over the other vital areas where action is needed, like the jobs market, and relaunching the economy.

![[Long read] Tunisia's revolutionary spirit, four years on [Long read] Tunisia's revolutionary spirit, four years on](https://static.euronews.com/articles/302960/1200x675_302960.jpg)